Manny Machado does so many fantastic things on a baseball diamond night in and night out that it's hard to keep track. If you're not paying close attention, you may very well miss a spectacular play at any point - whether Machado is playing shortstop or third base, or if he's standing at the plate.

Unfortunately, if Machado is on the basepaths, you might miss something not quite as spectacular. He's made at least several questionable baserunning decisions this season, which is peculiar for one of the very best players in the game.

All things considered, Machado might just be the best third baseman or shortstop in the game. He's clearly the best who can play both positions. So these baserunning mistakes are certainly not ideal, but when combined with everything else that Machado brings to the table, this may appear to be nit-picking. But I'm not really even doing that; I'm just taking a closer look at some bizarre decisions when he's on base. It also shouldn't take long to notice a theme.

Here's an early April play against the Rays. Chris Davis is at the plate, and Machado gets picked off:

Hey, pick-offs happen. Machado was clearly going to take off for second base, so this was a nice play by Jake Odorizzi and the great Steve Pearce.

A couple days later, with the Orioles trailing 4-2 in the sixth inning against the Red Sox, Machado took off for third base with two outs and Davis again up to bat. He didn't make it.

Stealing third without a good jump is difficult enough, but it's even tougher when the right-handed batter's box is open. Machado likely made up his mind at some point during the at-bat that he was going to take off (possibly because of the shift the Red Sox were deploying). Not only didn't it work, but it came in a key spot.

Getting thrown out at third with two outs and Davis up once wasn't enough, so Machado did it again a couple weeks later in Kansas City.

This isn't as bad as the attempted steal in Boston, and it is a better play overall (with a superb pick by Mike Moustakas). Machado doesn't always have great instincts in these situations, and maybe that's something in which he improves. Machado isn't lightning quick, but that's not all it takes to be an effective baserunner.

Still, not only is Machado giving up free outs on the basepaths -- three times now with Davis at the dish. But as you can see in his slide above, he took an unintentional knee to the face, so some of these plays are putting him at extra risk of getting injured. Sure, a player could get hurt on any number of plays -- perhaps just landing on the first base bag wrongly, as Machado has already done -- but there's no reason to do so on plays that only offer a minor benefit.

In May, in a third-inning situation with runners at the corners, two outs, and trailing 1-0 -- and Chris Davis AGAIN at-bat -- Machado seemed to attempt a delayed steal from first base.

At least, I hope that was a delayed steal in an attempt to get the runner from third to score before Machado is tagged out. Roch Kubatko of MASN noted that that's what it was. Regardless, that's a strange thing to do in the third inning with one of the Orioles' best hitters at the plate. That's also the fourth time that's happened.

And here's the most recent baserunning mistake by Machado. Leading by a run in the top of the fifth, Machado leads off by crushing a pitch that slams off the right-center field wall.

The ball briefly gets away from the two outfielders, so Machado makes a dash for third. He didn't make it. You might not believe it, but Davis was due to bat next.

-----

I'm not going to say Machado is a bad baserunner. He's also done things like this during the season, so he's capable of smart decisions and huge plays. However, for his career, he rates as a below average baserunner (-1.6 using FanGraphs' BsR metric) and has been thrown out on 18 of his 48 steal attempts. A success rate of 63% suggests he should stop stealing altogether, or at least that he needs to get much better at picking his spots. Despite his mistakes this season, he still surprisingly rates above average this season (0.6 BsR) and was also above average last year (1.1).

If there's going to be one thing Machado seems to struggle with, then at least it's his skills on the bases. Regardless, there is clearly room for improvement. My guess is that Chris Davis would agree.

31 May 2016

30 May 2016

Why You Should Care That The Orioles Traded A Draft Pick

This is a guest post by Jeff Long of Baseball Prospectus. You can find his work here and follow him on Twitter.

As I write this (before Sunday's win over the Indians), the Orioles sit at 27-20; one game behind the Red Sox in the AL East and right in the thick of the race among some of the best teams in the American League thus far. We’re just over a quarter of the way through the season, but surprise starts from teams like the Mariners and the White Sox have muddied the (very-early) playoff picture.

It’s been a terrific start for an Orioles club that faced a lot of questions coming into the season. The team spent a lot of money—their Opening Day payroll went up nearly $30 million from Opening Day 2015—to essentially field the same club as last year. The 2015 version of the Orioles finished 81-81, a dozen games back in the division and five out of the Wild Card. It was a disappointing season, and the team didn’t have any significant upgrades coming into 2016.

All of this is to say that performance to date might not reflect the team’s actual chances of making the playoffs and battling for the World Series. As of this writing, Baseball Prospectus has the Orioles with a roughly 26% chance of making the playoffs. That projection—based on BP’s PECOTA projection system—lands the Orioles fourth in the division behind the Rays (34%), Blue Jays (42%), and Red Sox (76%) respectively. Lest you think this means that PECOTA is down on the Orioles, that number represents a roughly 18 percentage point increase from their preseason playoff odds of 8%. Matt Trueblood worded PECOTA’s opinion thusly, They’ve gone from a very long shot to a legitimate contender, which is significant progress. From here, they have an honest chance to make a run at the postseason. That they aren’t a favorite is affirmation that, yes, some things are starting to carry real meaning, but it’s still early.

This is an elaborate (314 words, if you’re counting) way of saying that the Orioles have a shot at the playoffs. It may not be a great one, but it’s a shot.

This is critically important, because of the way that the team’s front office is running the club. They’ve largely thrown all of their eggs into the 2016/2017 basket; the future be damned. Trading draft picks and international bonus slots is simply their modus operandi in its most basic form.

I won’t get into the details, but it’s important that we understand that moves like the Brian Matusz or Ryan Webb trades are simply salary dumps wherein draft picks are exchanged for cold hard cash. This approach has ramifications that Dave Cameron summarized well:

OK, sure. Perhaps the $3 million or so the club saved by not designating Matusz for Assignment will be used to acquire someone that will help them make the playoffs this season. Here’s the simple problem with that argument. Nobody outside the warehouse knows where that money goes. Did Webb’s salary go to Parra? Maybe. Did they really need to save the money knowing that their Opening Day salary went up 10 times that between last season and this one? Probably not.

Whether or not the Orioles need to save the money is something that frankly we won’t ever have the answer to. What we do know is that they have a long history of trading away the opportunity to acquire players and pay them paltry minor league salaries. Let’s take a trip down memory lane, shall we?

Do you remember that time the Orioles traded Jake Arrieta and Pedro Strop to the Cubs for Scott Feldman and Steve Clevenger? They also sent the Cubs multiple international bonus slots to sweeten the deal. In fairness, it’s not like the Orioles were going to use them anyway, their international spending is often pathetic (with the exception of Asia, generally speaking).

I mentioned it previously, but they sent Ryan Webb and the 74th pick in the 2015 draft to the Dodgers so they wouldn’t have to pay his $2.8 million salary upon cutting him. The Orioles said, at the time, that they liked the "prospects" they got back in the deal, though those players are org guys who are unlikely to ever appear on a major-league roster. Stop me if this sounds familiar.

Then there was that time the Orioles traded two slots to the Astros for Chris Lee, who at least seems interesting, unlike previous acquisitions.

Then came the Matusz trade, followed swiftly by a dumping of international bonus slots to the Reds for a 23-year-old pitcher who hasn’t gotten past A-ball yet.

The problem with the Webb and Matusz trades of course is that those issues were completely avoidable. Both players were deemed to be DFA candidates during the offseason, when the club could have cut them without incurring financial penalties. Instead, they kept them on the roster and opted to pay a hefty price for their removal later.

The problem is sizable. As long as the major-league team keeps winning though, why should you care? Sustainability, that’s why.

Building a sustainable winner is a difficult task. Still, there are dozens of models to follow. You could look at the Cardinals who eschew veteran free agents in favor of a well-stocked farm system that produces impact player after impact player. This takes significant resources, but the club seem to deem it worthwhile. You could be like the Pirates and sign your young talent to long term deals, creating a cost-controlled core around which you can build. This too keeps costs down, but requires proactivity with contract negotiations. You could even follow a Red Sox model where free spending and free agency are the means by which wins are acquired. Even the Red Sox though, have a robust farm system stocked with future talent. The Orioles do not.

According to Baseball Prospectus, the Orioles have the 26th best farm system in baseball. Baseball America has them 27th. Keith Law of ESPN agrees, slotting the club at 27th. Across the board, the comments are the same. The club has some interesting talent in short season or A-ball, but those players are a long way off. The upper minors is filled with org guys and AAAA stars, guys who look good but aren’t likely to help the major-league team in a significant way.

They can’t seem to develop pitching properly, as their top pitching prospects routinely get hurt and underwhelm. Any interesting hitting prospects tend to get moved in trades, and the ones that have stayed are too few to be a true core to build around.

If you’re looking to the farm system for reinforcements or help either this season or down the road, you’ll be left wanting.

The farm system being down is a bigger problem than it seems of course. Who exactly is the team trading for veteran help at the deadline? Dave Cameron’s argument that these moves can help them win more games this season is built on a weak foundation given that the club hardly has the assets to acquire impactful talent in the first place.

The future? That’s bleak too. Matt Wieters is a free agent next season. The club will likely let him walk, with or without a qualifying offer. Mark Trumbo too, is a free agent-to-be. Chris Tillman’s team control ends in 2018, the following season, along with Hyun Soo Kim and Ubaldo Jimenez (which, let’s be honest, is probably a good thing). In 2019 both Adam Jones and Manny Machado will be free agents, along with Zach Britton who has grown into one of the best relievers in baseball.

Some of those changes are a ways away, but the fact remains that there are almost no replacements for these players in the minor leagues. They’ll need to come from somewhere, but with the club shredding draft picks and international bonus slots at every opportunity, it’s unclear from where.

The period from the late 1990s through 2012, an abysmal black hole in the franchise’s history, was set up with many of the same moves that this Orioles’ team is now engaging in. The team ignored the minors in hopes of capturing a World Series with its aging veteran talent. It didn’t work out, and the subsequent cliff was steep. It took the team more than a decade to dig out of that cliff.

The problem is that 2016, 2017, or maybe 2018 look a lot like the edge of the cliff that the team faced in 1997. My suggestion is that you hope and pray that the team wins a World Series sooner rather than later, because their odds of doing so in each subsequent season are getting worse and worse. I’m all for the win-now attitude this team has; I just hope they actually do win now, because I’m not optimistic about their chances of winning in the future.

As I write this (before Sunday's win over the Indians), the Orioles sit at 27-20; one game behind the Red Sox in the AL East and right in the thick of the race among some of the best teams in the American League thus far. We’re just over a quarter of the way through the season, but surprise starts from teams like the Mariners and the White Sox have muddied the (very-early) playoff picture.

It’s been a terrific start for an Orioles club that faced a lot of questions coming into the season. The team spent a lot of money—their Opening Day payroll went up nearly $30 million from Opening Day 2015—to essentially field the same club as last year. The 2015 version of the Orioles finished 81-81, a dozen games back in the division and five out of the Wild Card. It was a disappointing season, and the team didn’t have any significant upgrades coming into 2016.

All of this is to say that performance to date might not reflect the team’s actual chances of making the playoffs and battling for the World Series. As of this writing, Baseball Prospectus has the Orioles with a roughly 26% chance of making the playoffs. That projection—based on BP’s PECOTA projection system—lands the Orioles fourth in the division behind the Rays (34%), Blue Jays (42%), and Red Sox (76%) respectively. Lest you think this means that PECOTA is down on the Orioles, that number represents a roughly 18 percentage point increase from their preseason playoff odds of 8%. Matt Trueblood worded PECOTA’s opinion thusly, They’ve gone from a very long shot to a legitimate contender, which is significant progress. From here, they have an honest chance to make a run at the postseason. That they aren’t a favorite is affirmation that, yes, some things are starting to carry real meaning, but it’s still early.

This is an elaborate (314 words, if you’re counting) way of saying that the Orioles have a shot at the playoffs. It may not be a great one, but it’s a shot.

This is critically important, because of the way that the team’s front office is running the club. They’ve largely thrown all of their eggs into the 2016/2017 basket; the future be damned. Trading draft picks and international bonus slots is simply their modus operandi in its most basic form.

I won’t get into the details, but it’s important that we understand that moves like the Brian Matusz or Ryan Webb trades are simply salary dumps wherein draft picks are exchanged for cold hard cash. This approach has ramifications that Dave Cameron summarized well:

If Peter Angelos just pockets the $3 million, and the team doesn’t reallocate this money back into the franchise, then it’s perfectly reasonable for Orioles fans to be annoyed by this trend of the team selling draft picks. Making a habit out of reducing your prospect stock isn’t a great idea if you’re not using those prospects to acquire other things of value, and if shedding Matusz’s contract just allows Angelos to go buy some fancy art, well, that would suck for the franchise. But at this point, with the Orioles as likely buyers this summer and some obvious holes on the roster, I think it’s probably best to assume that this is a move made in preparation for taking on big league salary in July.There are a few components to this that are worth exploring in more detail. Cameron suggests that the Orioles’ trading of draft picks for money gives them more flexibility to take on salary at the July trade deadline. The argument, in hindsight, is often that the trading of Ryan Webb’s salary led to the acquisition of Gerardo Parra who helped (Parra actually cost the Orioles wins with his performance, but nevermind that for now) the team down the stretch run.

And if that’s the case, then all the Orioles are really doing is trading a prospect for some help at the big-league roster, which is exactly what we expect teams in first place to do.

Dave Cameron – The Orioles Sold a Draft Pick Again

OK, sure. Perhaps the $3 million or so the club saved by not designating Matusz for Assignment will be used to acquire someone that will help them make the playoffs this season. Here’s the simple problem with that argument. Nobody outside the warehouse knows where that money goes. Did Webb’s salary go to Parra? Maybe. Did they really need to save the money knowing that their Opening Day salary went up 10 times that between last season and this one? Probably not.

Whether or not the Orioles need to save the money is something that frankly we won’t ever have the answer to. What we do know is that they have a long history of trading away the opportunity to acquire players and pay them paltry minor league salaries. Let’s take a trip down memory lane, shall we?

Do you remember that time the Orioles traded Jake Arrieta and Pedro Strop to the Cubs for Scott Feldman and Steve Clevenger? They also sent the Cubs multiple international bonus slots to sweeten the deal. In fairness, it’s not like the Orioles were going to use them anyway, their international spending is often pathetic (with the exception of Asia, generally speaking).

I mentioned it previously, but they sent Ryan Webb and the 74th pick in the 2015 draft to the Dodgers so they wouldn’t have to pay his $2.8 million salary upon cutting him. The Orioles said, at the time, that they liked the "prospects" they got back in the deal, though those players are org guys who are unlikely to ever appear on a major-league roster. Stop me if this sounds familiar.

Then there was that time the Orioles traded two slots to the Astros for Chris Lee, who at least seems interesting, unlike previous acquisitions.

Then came the Matusz trade, followed swiftly by a dumping of international bonus slots to the Reds for a 23-year-old pitcher who hasn’t gotten past A-ball yet.

The problem with the Webb and Matusz trades of course is that those issues were completely avoidable. Both players were deemed to be DFA candidates during the offseason, when the club could have cut them without incurring financial penalties. Instead, they kept them on the roster and opted to pay a hefty price for their removal later.

The problem is sizable. As long as the major-league team keeps winning though, why should you care? Sustainability, that’s why.

***

Building a sustainable winner is a difficult task. Still, there are dozens of models to follow. You could look at the Cardinals who eschew veteran free agents in favor of a well-stocked farm system that produces impact player after impact player. This takes significant resources, but the club seem to deem it worthwhile. You could be like the Pirates and sign your young talent to long term deals, creating a cost-controlled core around which you can build. This too keeps costs down, but requires proactivity with contract negotiations. You could even follow a Red Sox model where free spending and free agency are the means by which wins are acquired. Even the Red Sox though, have a robust farm system stocked with future talent. The Orioles do not.

According to Baseball Prospectus, the Orioles have the 26th best farm system in baseball. Baseball America has them 27th. Keith Law of ESPN agrees, slotting the club at 27th. Across the board, the comments are the same. The club has some interesting talent in short season or A-ball, but those players are a long way off. The upper minors is filled with org guys and AAAA stars, guys who look good but aren’t likely to help the major-league team in a significant way.

They can’t seem to develop pitching properly, as their top pitching prospects routinely get hurt and underwhelm. Any interesting hitting prospects tend to get moved in trades, and the ones that have stayed are too few to be a true core to build around.

If you’re looking to the farm system for reinforcements or help either this season or down the road, you’ll be left wanting.

The farm system being down is a bigger problem than it seems of course. Who exactly is the team trading for veteran help at the deadline? Dave Cameron’s argument that these moves can help them win more games this season is built on a weak foundation given that the club hardly has the assets to acquire impactful talent in the first place.

The future? That’s bleak too. Matt Wieters is a free agent next season. The club will likely let him walk, with or without a qualifying offer. Mark Trumbo too, is a free agent-to-be. Chris Tillman’s team control ends in 2018, the following season, along with Hyun Soo Kim and Ubaldo Jimenez (which, let’s be honest, is probably a good thing). In 2019 both Adam Jones and Manny Machado will be free agents, along with Zach Britton who has grown into one of the best relievers in baseball.

Some of those changes are a ways away, but the fact remains that there are almost no replacements for these players in the minor leagues. They’ll need to come from somewhere, but with the club shredding draft picks and international bonus slots at every opportunity, it’s unclear from where.

The period from the late 1990s through 2012, an abysmal black hole in the franchise’s history, was set up with many of the same moves that this Orioles’ team is now engaging in. The team ignored the minors in hopes of capturing a World Series with its aging veteran talent. It didn’t work out, and the subsequent cliff was steep. It took the team more than a decade to dig out of that cliff.

The problem is that 2016, 2017, or maybe 2018 look a lot like the edge of the cliff that the team faced in 1997. My suggestion is that you hope and pray that the team wins a World Series sooner rather than later, because their odds of doing so in each subsequent season are getting worse and worse. I’m all for the win-now attitude this team has; I just hope they actually do win now, because I’m not optimistic about their chances of winning in the future.

BORT: Brian Matusz And A Lost Pick

In March of 2009, the local Orioles blogosphere was in its primordial golden epoch where sites were plentiful and largely operated by only a person or two. Back then, I developed the Baltimore Orioles Round Table to make the community more cohesive and increase audience awareness for other sites. Now, the lone person writing for an Orioles site is not so common anymore. We all have large stables. In this current incarnation, the objective is not to increase awareness between sites, but to provide multiple slants at a single issue. Enjoy!

The Brian Matusz trade and Dan Duquette's willingness to deal draft picks.

Participants: Elie Waitzer, Patrick Dougherty, Avi Miller

Elie Waitzer: The Orioles got two Minor League arms - Brandon Barker and Trevor Belicek - from the Braves in exchange for Brian Matusz, but the real swap had nothing to do with any of those players. Atlanta immediately DFA'd Matusz, and the neither of the arms were thought of as prospects. If you want to read about how Barker and Belicek might pan out, Chris Mitchell did a good write up on Fangraphs.

The Brian Matusz trade and Dan Duquette's willingness to deal draft picks.

Participants: Elie Waitzer, Patrick Dougherty, Avi Miller

Elie Waitzer: The Orioles got two Minor League arms - Brandon Barker and Trevor Belicek - from the Braves in exchange for Brian Matusz, but the real swap had nothing to do with any of those players. Atlanta immediately DFA'd Matusz, and the neither of the arms were thought of as prospects. If you want to read about how Barker and Belicek might pan out, Chris Mitchell did a good write up on Fangraphs.

Broken down into simple terms, this was a creative win-now/win-later trade between Dan Duquette and Braves GM John Coppolella. Baltimore got present-day financial flexibility by offloading the remaining $3M of Matusz contract. Atlanta got future financial flexibility in the form of an additional $830K in bonus pool allocation that comes with the 76th draft pick that will allow the Braves to be more aggressive in the draft.

This is clearly not a stand-alone trade, and it's how Duquette springboards off of this move that will determine whether it was worth it for the Orioles to reduce their ability to potentially grab better talent in mid-late rounds of the drafts (with the 27th, 54th, and 69th picks.)

The best case scenario is that the $3M in savings will give Duquette some extra wiggle room at the trade deadline to make the O's a more attractive trading partner for teams looking to deal starting pitching. The ability to take on more of a player's contract gives Baltimore an edge over other teams, and makes up in part for the fact that they won't be able to offer the kind of prospects other teams will (Keith Law ranked the O's farm system 27th at the start of 2016).

Before the start of the season, Matt Kremnitzer looked at the best and worst cases for the rotation and set a pessimistic tone by referencing Fangraphs' dismal projections for the O's starters. Despite their collective 3.80 ERA, the ragtag starting staff has vastly outperformed expectations, ranking ninth in the league by total WAR (3.9) thus far. But the pleasant start has been fueled largely by strong starts from Chris Tillman and Kevin Gausman, not by solid depth 1 through 5. If this move leads (or partially leads) to the O's landing rotation help in the form of James Shields, Rich Hill, Jimmy Nelson, or any solid arm that can take innings away from Mike Wright and Tyler Wilson, I'll consider it a win. Until then, the jury is out.

Patrick Dougherty: They say to trust your gut, and with a few days to think on this deal, I feel the same way I did when my phone buzzed with the notification. Brian Matusz has been a non-factor for the Orioles for years, and taking his $3.9 million salary (or the $3M of it that the Braves will assume) off the books is, in a vacuum, a win. I thought the Orioles were overpaying for Matusz when they made the one-year deal to avoid arbitration because I didn't think of him as anything more than a mediocre LOOGY (lefties have hit him for a .276 average in his career, although Matusz has successfully stayed away from giving lefties walks or home runs). Apparently, the team thought Matusz could work his way into a less specialized bullpen role, or at least into a decent return in a trade. Clearly, he could not.

The minor good of ridding the team of a player who directly affects about 3% of the Orioles' innings in a year (50 IP/1,458 innings in 162 9-inning games) is vastly outweighed by the bad of giving up the 76th pick in next year's draft. The stars-and-scrubs method of roster construction is highly variant and, in my opinion, a mistake to pursue. Particularly for a team that is in one of the smallest markets in the league and likes to paint itself as being cash-strapped, the best way to build a competitive roster is through drafting and developing well. The Orioles do neither.

In some cases, I may be tempted to argue that because the Orioles have proven themselves to be largely incapable of drafting and developing players, particularly pitchers, it makes sense for the team to ditch picks in favor of cash with which to bring in arms that have learned the game elsewhere. That specialization of labor model might be attractive if the Orioles sat atop a pile of cash the way the Yankees or the Dodgers do, but I'm tired of making the argument in favor of giving up on what is the Orioles' most obvious path for continued, cheap success.

Instead, I'll go in the opposite direction. Because the Orioles are ineffective drafters, they should be taking a shotgun approach: take the best players available as often as possible and pray that one of them becomes the exception to the organization's deflating rule.

If I sound fed up, I am. During the offseason, the Warehouse talks about the importance of draft picks and why the team just can't give them up to sign premiere free agents who were extended qualifying offers. This Matusz trade marks the second time in two years that the organization has given away a pick to dump the relatively meager salary of an average reliever (not to mention the pick given up for Bud Norris and the many international signing slots the team has traded away in recent years).

The Matusz trade is, in my opinion, a failure both in terms of the potential that the team jettisoned by trading away a competitive balance pick, and in terms of continuing the Orioles' precedent of undervaluing draft picks. I don't believe $3 million in wiggle room is going to allow the team to bring in a stud pitcher at the deadline; they cost a lot more than that, and the budget is already stretched, as far as anyone outside the Warehouse knows. I do believe that the team consistently undervalues draft picks - or realizes that they're so bad with them that they're using them as currency because they've given up.

Avi Miller: So why exactly did the Orioles even tender Matusz heading into 2016? Complaints abound among the Baltimore fan base, Dan Duquette knew very well that Matusz would command a fourth-year arbitration salary above $3.2 million, his 2015 earnings.

Matusz, despite popular belief, could have been a very serviceable middle relief arm in 2015. Though his career average against when facing left-handed hitters is .276, as Patrick noted, I redirect your attention to his 2015 showing against that same group: .185/.231/.333 across 109 batters faced.

Thus, as a LOOGY, Matusz slotted in quite nicely. Even when he took the mound against almost the equivalent number of batters in the right-handed batter's box, the results were not dreadful: .238/.375/.346 across 97 batters faced (16 walks killed him against this group).

So a salary expectation in the mid-$3 million range for a left-hander after a 49-inning season to the tune of a 2.94 ERA wasn't absurd, to say the least. And here's why.

| Name | Games | Innings Pitched | ERA | FIP | xFIP | fWAR | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | BABIP | GB% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brian Matusz | 186 | 151.2 | 3.32 | 3.50 | 3.87 | 1.8 | 9.44 | 3.15 | 0.89 | .289 | 36.4% |

| Tony Sipp | 172 | 142.2 | 3.22 | 3.45 | 3.63 | 1.7 | 10.54 | 3.41 | 1.01 | .253 | 32.6% |

| Zach Duke | 171 | 150.2 | 3.58 | 3.57 | 3.16 | 1.1 | 9.44 | 3.52 | 0.90 | .301 | 55.9% |

The table above compares Matusz to two other notable lefty relievers, Tony Sipp and Zach Duke. The numbers shown are from the 2013-2015 seasons.

Tony Sipp, a veteran who had a choppy history with both Cleveland and Arizona before settling in Houston a couple years ago, signed a three-year, $18 million contract to return to the Astros prior to the 2016 campaign.

Zach Duke, taking an even bumpier road starting in Pittsburgh back in 2005, earned a three-year, $15 million contract with the White Sox two offseasons ago.

As such, Brian Matusz was on his way to a nice little payday following the 2016 season. How he gets there now is a bit more in question.

26 May 2016

You Don't Have To Like The Orioles Striking Out So Much, But You Knew It Was Going To Happen

I hope you're sitting down when you read this: The Orioles assembled a team of power hitters, and they are striking out a lot. Sometimes, they are going to have games where they impress with powerful home run displays. They've done that. Other times, they are going to frustrate and run off stretches when they're not scoring a bunch of runs and look lost at the plate. They're in the middle of one of those brutal stretches right now, and Tuesday night's 19-strikeout, extra-inning loss was a prime, tough-to-watch example. They even managed to follow that up by striking out 18 times in nine innings on Wednesday.

Apparently Tuesday's struggles frustrated some more than others. Peter Schmuck of The Baltimore Sun singled out Adam Jones's quote in this Jon Meoli story about strikeouts being "part of [the Orioles'] DNA as a team." As usual, Jones had other interesting things to say, but it's not all that surprising that someone focused on the DNA comment and wrote something negative about it.

No one likes to see his or her favorite team's hitters constantly flail away at the plate, especially in crucial situations. It's maddening. As of last night, the O's were 10th in the majors in strikeout percentage, so surely fans of the teams above them feel similarly at times just as often, if not more.

Maybe Schmuck's angle is that O's batters shouldn't accept their whiffing ways, or that saying they're going to strike out means they aren't doing anything to prevent it. Or maybe the larger point is about wanting games to be more aesthetically pleasing (more balls in play, etc.) instead of swing and miss after swing and miss. The former seems ridiculous, but perhaps the latter is a discussion worth having. I don't really share that opinion, but many do.

Anyway, unless you really think Jones's comments mean the O's aren't trying or aren't striving to get better, then nothing about what the Orioles have done at the plate should be surprising. They rank 10th in runs per game in the majors, and the goal is still to score as many runs as possible. Maybe they should even be striking out more, considering the various free-swinging sluggers in their lineup.

In a March post for FanGraphs -- titled "Are the Orioles Going to Strike Out Too Much?" because everyone knew the Orioles put together a lineup full of windmills -- Dave Cameron noted that "team strikeout rate doesn’t really have a negative impact on the number of runs a team scores relative to expectations" before moving on to an analysis of extreme strikeout teams underperforming their BaseRuns projections.

Along those lines, it's reasonable to worry about the team's level of production in clutch situations as the season goes along, because high-strikeout teams might not be as good in that department. But it is silly for Schmuck to assert that "opposing advance scouts just [discovered] how vulnerable the Orioles are to a steady diet of offspeed stuff that breaks under and around the strike zone." The O's are a collection of mostly veteran players that have been heavily scouted, so give both them, the pitchers they are facing, and advanced scouts more credit than that. You don't think teams in the American League East know several O's hitters are vulnerable to pitches out of the strike zone? If not, then they need new scouts.

The Orioles haven't looked good at the plate lately. Some of that is the result of a long season, with normal ebbs and flows. Some of that is because this is what the O's lineup will occasionally look like. And some of that is because of certain players getting more playing time than they probably should, or batting in non-optimal spots in the lineup. The O's roster has holes that Buck Showalter can't hide.

In both 2014 and 2015, the O's were in the top 10 of highest strikeout percentage teams, and they still finished with top 10 offenses. In 2013, the O's were much lower in strikeouts (23rd) but placed fifth in runs scored. None of those teams won the World Series, because the number of strikeouts isn't the sole determinant of who prevails and who doesn't.

If you want to criticize anything, then rail against how this team was put together. But considering that the O's are still eight games above .500, that would be strange timing.

Apparently Tuesday's struggles frustrated some more than others. Peter Schmuck of The Baltimore Sun singled out Adam Jones's quote in this Jon Meoli story about strikeouts being "part of [the Orioles'] DNA as a team." As usual, Jones had other interesting things to say, but it's not all that surprising that someone focused on the DNA comment and wrote something negative about it.

No one likes to see his or her favorite team's hitters constantly flail away at the plate, especially in crucial situations. It's maddening. As of last night, the O's were 10th in the majors in strikeout percentage, so surely fans of the teams above them feel similarly at times just as often, if not more.

Maybe Schmuck's angle is that O's batters shouldn't accept their whiffing ways, or that saying they're going to strike out means they aren't doing anything to prevent it. Or maybe the larger point is about wanting games to be more aesthetically pleasing (more balls in play, etc.) instead of swing and miss after swing and miss. The former seems ridiculous, but perhaps the latter is a discussion worth having. I don't really share that opinion, but many do.

Anyway, unless you really think Jones's comments mean the O's aren't trying or aren't striving to get better, then nothing about what the Orioles have done at the plate should be surprising. They rank 10th in runs per game in the majors, and the goal is still to score as many runs as possible. Maybe they should even be striking out more, considering the various free-swinging sluggers in their lineup.

In a March post for FanGraphs -- titled "Are the Orioles Going to Strike Out Too Much?" because everyone knew the Orioles put together a lineup full of windmills -- Dave Cameron noted that "team strikeout rate doesn’t really have a negative impact on the number of runs a team scores relative to expectations" before moving on to an analysis of extreme strikeout teams underperforming their BaseRuns projections.

Along those lines, it's reasonable to worry about the team's level of production in clutch situations as the season goes along, because high-strikeout teams might not be as good in that department. But it is silly for Schmuck to assert that "opposing advance scouts just [discovered] how vulnerable the Orioles are to a steady diet of offspeed stuff that breaks under and around the strike zone." The O's are a collection of mostly veteran players that have been heavily scouted, so give both them, the pitchers they are facing, and advanced scouts more credit than that. You don't think teams in the American League East know several O's hitters are vulnerable to pitches out of the strike zone? If not, then they need new scouts.

The Orioles haven't looked good at the plate lately. Some of that is the result of a long season, with normal ebbs and flows. Some of that is because this is what the O's lineup will occasionally look like. And some of that is because of certain players getting more playing time than they probably should, or batting in non-optimal spots in the lineup. The O's roster has holes that Buck Showalter can't hide.

In both 2014 and 2015, the O's were in the top 10 of highest strikeout percentage teams, and they still finished with top 10 offenses. In 2013, the O's were much lower in strikeouts (23rd) but placed fifth in runs scored. None of those teams won the World Series, because the number of strikeouts isn't the sole determinant of who prevails and who doesn't.

If you want to criticize anything, then rail against how this team was put together. But considering that the O's are still eight games above .500, that would be strange timing.

25 May 2016

What Happened To Brian Matusz?

Here's what’s crazy about the Brian Matusz situation: he was good last year. Legitimately good. Just last year! Against 206 batters, split nearly evenly between righties and lefties, he had a solid 71 ERA-, 85 FIP-, and 98 xFIP-. His K-BB rate was an excellent 17.5%, nearly 30% better than a league-average reliever.

But he couldn’t find it again in 2016. Against 35 batters he put up an ERA- of 290, FIP-, of 303, and xFIP- of 248. That’s while striking out a paltry 2.9% (just one batter!) and walking an astounding 20%. On top of that, he surrendered three HR in six innings, with two coming in the same game.

It's just six innings, but -- what the hell happened?

Matusz stopped throwing strikes. Hitters waited him out, taking their walks, and crushed what he gave them, refusing to strike out. The speed with which hitters caught up to him, and the severity with which they tagged him, is odd to me. Matusz was never stellar but he was never this bad.

His Zone% plummeted:

Hitters didn't chase like they did in 2015. In particular, they spat on his fastball and slider, which he'd used as strikeout pitches:

But he couldn’t find it again in 2016. Against 35 batters he put up an ERA- of 290, FIP-, of 303, and xFIP- of 248. That’s while striking out a paltry 2.9% (just one batter!) and walking an astounding 20%. On top of that, he surrendered three HR in six innings, with two coming in the same game.

It's just six innings, but -- what the hell happened?

Matusz stopped throwing strikes. Hitters waited him out, taking their walks, and crushed what he gave them, refusing to strike out. The speed with which hitters caught up to him, and the severity with which they tagged him, is odd to me. Matusz was never stellar but he was never this bad.

His Zone% plummeted:

Hitters didn't chase like they did in 2015. In particular, they spat on his fastball and slider, which he'd used as strikeout pitches:

In 2015, these two pitches accounted for 50 strikeouts and 12 walks of 206 batters, amounting to a 24.2% K rate and 5.8% walk rate.

In 2016, these pitches accounted for one strikeout and seven walks of 35 batters, for terrible 2.8% strikeout and 20% walk rates.

When they did get a pitch to their liking, batters didn’t miss. Opponents' Z-Contact% jumped from 67.2% to 75.8%.

Hitters connected with his fastball and change-up more often:

When they connected, they did more damage:

These weren't fluke hits. Exit velocity shows Matusz's fastball, and to some extent his change-up, were very hittable:

Whew. That's a pretty ugly story. The speed and magnitude of hitters' adjustment to Matusz astounds me. Was it bad luck? Poor sequencing? It wasn't velocity; his fastball was down about 0.80 MPH, which isn't good, but that drop isn't enough to explain the graphs above. And his other pitches were flat or even up. His horizontal release points separated out a bit compared to last year, but again, could those fractions of an inch really make that much of a difference?

The first graph tells the story to me: Matusz lost his command. He couldn't locate his fastball like he used to in order to put hitters away. That, and perhaps some pitch-tipping (or amazing advance scouting) led to hitters laying off the heater and the slider because they were ahead in the count. Thus the high walk rate and increased damage on pitches in the zone.

Finally, his HR/FB rate of 30% indicates some bad luck. Matusz had been keeping the ball on the ground better than ever before; his GB/FB rate of 1.10 was the highest of his career. That's what you want to see from a pitcher who's not striking out a lot of batters.

He'll be back in the majors. Matusz is left-handed, 29 years old, and making reasonable money. He's one season removed from a good year and his struggles came on so rapidly and sharply that other teams may see them as a fluke. Besides, his stinker of a 2016 is only six innings.

Plus, he's coming from the Orioles. Some team is bound to look at him and think they can do what the Cubs did to Jake Arrieta. Neither the Orioles nor the Braves need him, but there are 28 more teams who might.

Fare thee well, Brian Matusz. You never lived up to your promise as the number four overall pick, but you were a good reliever for a few years and you deserve a tip of the cap from this fanbase.

24 May 2016

Looking Back At Fangraphs' Projections

After a fourth of the season is in the books, the Orioles are 26-16 and have the second highest winning percentage in the majors. Naturally, this vindicates Fangraphs which projected that the Orioles would win the AL East this year. Wait, what’s that you say? Oh yeah, they projected the Orioles to be in last place and not first. On the bright side, at least they didn’t project the Orioles to win 72 or 73 games. I guess the obvious question to ask is what happened.

For starters, it’s worth noting that the Orioles aren’t their largest miss. When comparing their actual winning percentage to their projected winning percentage, Fangraphs has been worse when projecting the Twins (off by 21.9%), Phillies (off by 17.3%), Braves (off by 14.1%) and Astros (off by 15.9%). Meanwhile, Fangraphs projected the Orioles to have a 49.4% winning percentage and the Orioles actually have a 61.9% winning percentage. On average, Fangraphs is off by 6.77% or roughly 11 wins per team over a full season. If someone had projected that each team would go .500, then they’d be off by 7.73% or 12.5 wins per team over a full season. So far, Fangraphs has been more accurate than just presuming that each team would go .500, but not by very much. It is still early in the season though, but at the current moment, well.

As for the Orioles specifically, Fangraphs projected that the Orioles would score 4.64 runs per game and the Orioles have actually scored 4.55. The Orioles are on pace to score 15 runs fewer than Fangraphs projected. This is reasonably close and suggests that Fangraphs overestimated the Orioles offense. These results illustrate that the problem with their projection wasn’t runs scored. Rather, their problem was with runs allowed. Fangraphs projected that the Orioles would allow 4.69 runs per game. The Orioles have actually allowed 3.98 runs per game. The Orioles are on pace to allow 116 runs less than their March projections and 83 runs less than their current projections. If the Orioles can keep that up, then they’ll prove the computers wrong.

The reason for the discrepancy obviously comes on the pitching/defense side of things. But is it all of the pitching? Fangraphs originally projected that the Orioles starting pitching would pitch 935 innings, with a 4.38 ERA and thus give up 455 earned runs. So far, they’re actually doing pretty well with this prediction. The Orioles starting pitching is on pace to throw 914 innings with a 4.44 ERA and to give up 451 earned runs. The Orioles starting rotation would be on pace to allow 461 earned runs if it threw 935 innings. It’s pretty clear that Fangraphs has nailed the Orioles’ starting pitching so far.

The problem is that Fangraphs also projected that the Orioles bullpen would pitch 523 innings, with a 3.76 ERA and give up 218 runs. So far, the bullpen is on pace to pitch 521 innings, but with a 2.67 ERA and thus give up 154 runs. In addition, Fangraphs projected the Orioles to allow 86 unearned runs. So far, the Orioles have allowed 10 and are on pace to allow just 39. Back in March, I wrote an article discussing how Fangraphs projected standings is likely flawed due to how it accounts for unearned runs. It seems like that flaw has come back to bite them.

This flaw has a surprisingly large impact. Using a t-test, Fangraphs' projected runs allowed on the team level is statistically different then the actual results so far (t>.9781). But Fangraphs' projected runs allowed and actual runs allowed by the starting rotation isn't statistically different (t>.1410). This is also the case for the bullpen (t>.2019) suggesting that they're doing a reasonably good job projecting starter and reliever performance. But a t-test comparing the amount of total unearned runs allowed by team to the projected number of unearned runs allowed by team is statistically different at the <.0001 level. Their inability to predict unearned runs significantly weakens the value of their runs allowed projections. Fangraphs' results in this regard are so poor that the Orioles aren't the most egregious case. The Royals, Indians and Rays are each on pace to outperform their projection by over 50 runs. They were projected on average to give up 77 unearned runs and are on pace to allow 21 each. That can't be good.

Using the Wayback Machine, since Fangraphs doesn’t save its original depth charts, it’s possible to review Fangraphs’ projections on March 11th, 2016. So far, a number of crucial pitchers in the bullpen have outperformed Fangraphs’ assumptions. For example, Fangraphs thought that Zach Britton would be good, and projected him to allow 19 earned runs while throwing 65 innings. Britton is on pace to allow 13 runs while throwing 76.66 innings. But Brach is the real lynchpin. Fangraphs projected Brach to give up 21.75 runs over 55 innings. Brach is on pace to give up 12.7 runs over 98.5 innings. That’s a 26 run swing right there, presuming he throws 98 innings in relief. Givens is on pace to give up 13 fewer runs than projected. McFarland, Bundy and Matusz are the only underperforming relievers and they’ve thrown 37 of the bullpens’ 135 innings. After those three, the reliever with the worst results is Darren O’Day with his 2.76 ERA.

Furthermore, the Orioles four elite relievers are throwing 60% of all the innings thrown by the bullpen despite being projected to throw 44% of the innings. Bullpens have better ERAs when their best pitchers throw more innings. That, combined with unexpectedly strong performances from Worley (0 ER in 14 innings as a reliever) and Wilson (1 ER in 8 innings as a reliever) has meant that the Orioles’ bullpen has vastly over performed.

On the defensive side, the Orioles may rank poorly in Fangraphs’ Def stat (20th in MLB), but they only allowed 18 errors in their first 42 games. The Orioles allow .55 unearned runs per error which is worse than league average. But they have the fifth lowest error per game ratio in MLB and is why the Orioles have given up so few unearned runs. On a simplistic level, if the Orioles continue to give up few errors, they’ll allow few unearned runs. On a more complex level, does this mean that the Orioles defense is better than it appears? The Orioles fielding weakness is corner outfield defense, which UZR may not be able to measure properly. Their BABIP is league average, but it would take an analysis to determine the type of batted-ball contact that their pitching has allowed. Further, Inside Edge noted in a blog post that the Orioles rank tenth in defensive giveaways.

The Orioles have outperformed Fangraphs expectations so far due to their excellent bullpen and their ability to avoid unearned runs. They have been slightly lucky, but it makes sense that a team with a strong bullpen will get lucky. Going forward, perhaps this suggests that the Orioles shouldn’t be focusing on adding starting pitching, but perhaps adding a good reliever to ensure the bullpen can continue performing at its current level. It’s pretty clear that the Orioles’ plan is to hope that their offense will maintain its current standard and that their bullpen can continue dominating.

For starters, it’s worth noting that the Orioles aren’t their largest miss. When comparing their actual winning percentage to their projected winning percentage, Fangraphs has been worse when projecting the Twins (off by 21.9%), Phillies (off by 17.3%), Braves (off by 14.1%) and Astros (off by 15.9%). Meanwhile, Fangraphs projected the Orioles to have a 49.4% winning percentage and the Orioles actually have a 61.9% winning percentage. On average, Fangraphs is off by 6.77% or roughly 11 wins per team over a full season. If someone had projected that each team would go .500, then they’d be off by 7.73% or 12.5 wins per team over a full season. So far, Fangraphs has been more accurate than just presuming that each team would go .500, but not by very much. It is still early in the season though, but at the current moment, well.

As for the Orioles specifically, Fangraphs projected that the Orioles would score 4.64 runs per game and the Orioles have actually scored 4.55. The Orioles are on pace to score 15 runs fewer than Fangraphs projected. This is reasonably close and suggests that Fangraphs overestimated the Orioles offense. These results illustrate that the problem with their projection wasn’t runs scored. Rather, their problem was with runs allowed. Fangraphs projected that the Orioles would allow 4.69 runs per game. The Orioles have actually allowed 3.98 runs per game. The Orioles are on pace to allow 116 runs less than their March projections and 83 runs less than their current projections. If the Orioles can keep that up, then they’ll prove the computers wrong.

The reason for the discrepancy obviously comes on the pitching/defense side of things. But is it all of the pitching? Fangraphs originally projected that the Orioles starting pitching would pitch 935 innings, with a 4.38 ERA and thus give up 455 earned runs. So far, they’re actually doing pretty well with this prediction. The Orioles starting pitching is on pace to throw 914 innings with a 4.44 ERA and to give up 451 earned runs. The Orioles starting rotation would be on pace to allow 461 earned runs if it threw 935 innings. It’s pretty clear that Fangraphs has nailed the Orioles’ starting pitching so far.

The problem is that Fangraphs also projected that the Orioles bullpen would pitch 523 innings, with a 3.76 ERA and give up 218 runs. So far, the bullpen is on pace to pitch 521 innings, but with a 2.67 ERA and thus give up 154 runs. In addition, Fangraphs projected the Orioles to allow 86 unearned runs. So far, the Orioles have allowed 10 and are on pace to allow just 39. Back in March, I wrote an article discussing how Fangraphs projected standings is likely flawed due to how it accounts for unearned runs. It seems like that flaw has come back to bite them.

This flaw has a surprisingly large impact. Using a t-test, Fangraphs' projected runs allowed on the team level is statistically different then the actual results so far (t>.9781). But Fangraphs' projected runs allowed and actual runs allowed by the starting rotation isn't statistically different (t>.1410). This is also the case for the bullpen (t>.2019) suggesting that they're doing a reasonably good job projecting starter and reliever performance. But a t-test comparing the amount of total unearned runs allowed by team to the projected number of unearned runs allowed by team is statistically different at the <.0001 level. Their inability to predict unearned runs significantly weakens the value of their runs allowed projections. Fangraphs' results in this regard are so poor that the Orioles aren't the most egregious case. The Royals, Indians and Rays are each on pace to outperform their projection by over 50 runs. They were projected on average to give up 77 unearned runs and are on pace to allow 21 each. That can't be good.

Using the Wayback Machine, since Fangraphs doesn’t save its original depth charts, it’s possible to review Fangraphs’ projections on March 11th, 2016. So far, a number of crucial pitchers in the bullpen have outperformed Fangraphs’ assumptions. For example, Fangraphs thought that Zach Britton would be good, and projected him to allow 19 earned runs while throwing 65 innings. Britton is on pace to allow 13 runs while throwing 76.66 innings. But Brach is the real lynchpin. Fangraphs projected Brach to give up 21.75 runs over 55 innings. Brach is on pace to give up 12.7 runs over 98.5 innings. That’s a 26 run swing right there, presuming he throws 98 innings in relief. Givens is on pace to give up 13 fewer runs than projected. McFarland, Bundy and Matusz are the only underperforming relievers and they’ve thrown 37 of the bullpens’ 135 innings. After those three, the reliever with the worst results is Darren O’Day with his 2.76 ERA.

Furthermore, the Orioles four elite relievers are throwing 60% of all the innings thrown by the bullpen despite being projected to throw 44% of the innings. Bullpens have better ERAs when their best pitchers throw more innings. That, combined with unexpectedly strong performances from Worley (0 ER in 14 innings as a reliever) and Wilson (1 ER in 8 innings as a reliever) has meant that the Orioles’ bullpen has vastly over performed.

On the defensive side, the Orioles may rank poorly in Fangraphs’ Def stat (20th in MLB), but they only allowed 18 errors in their first 42 games. The Orioles allow .55 unearned runs per error which is worse than league average. But they have the fifth lowest error per game ratio in MLB and is why the Orioles have given up so few unearned runs. On a simplistic level, if the Orioles continue to give up few errors, they’ll allow few unearned runs. On a more complex level, does this mean that the Orioles defense is better than it appears? The Orioles fielding weakness is corner outfield defense, which UZR may not be able to measure properly. Their BABIP is league average, but it would take an analysis to determine the type of batted-ball contact that their pitching has allowed. Further, Inside Edge noted in a blog post that the Orioles rank tenth in defensive giveaways.

The Orioles have outperformed Fangraphs expectations so far due to their excellent bullpen and their ability to avoid unearned runs. They have been slightly lucky, but it makes sense that a team with a strong bullpen will get lucky. Going forward, perhaps this suggests that the Orioles shouldn’t be focusing on adding starting pitching, but perhaps adding a good reliever to ensure the bullpen can continue performing at its current level. It’s pretty clear that the Orioles’ plan is to hope that their offense will maintain its current standard and that their bullpen can continue dominating.

23 May 2016

Book Club: The Only Rule Is It Has To Work

Disclaimer: Ben Lindbergh and I wrote this piece on Spring Training performance and the John Dewan Rule, so I know him somewhat. Sam Miller was my editor during my stint writing for Baseball Prospectus and we actually briefly discussed potential talent to acquire for the Stompers...very briefly.

Before computers were a staple in most homes, I had baseball cards. My favorite ones were not the sought after rookie cards, but those that covered a player's final season and all that came before. Rookie cards mattered if they included minor league seasons. Hours were then spent with my brother "drafting" teams, constructing lineups, piecing together rotations, and arguing which team was superior. We would create model ballparks and discuss differences between playing fields in how they impacted performance. That is what my brother and I did when it rained or snowed or if we were up at 1am and UHF channels were boring.

With that kernel to my being, Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller wrote a book that slots right into the more primordial substrates in my brain. In The Only Rule Is It Has To Work, the duo write about their experience in jockeying into position to run a professional baseball team for a season. No, they were not able to instruct the best players in the World at the MLB stage. Instead, they worked with a rung of very, very good baseball players; the kind that exist on the lower rungs of professional baseball. For a season, they ran baseball operations for the Sonoma Stompers.

While those familiar with the Baseball Prospectus and Five Thirty Eight writings of the two might expect an analytical book, that is not what this is. Yes, the authors underpin their choices with analysis, but that is not the focus. The focus is how exactly do you incorporate these ideas into an organization that would likely benefits from those ideas, but is greatly suspicious of your ability. In other words, this book is primarily a process oriented book about people without industry credibility figuring out how to implement change.

The preponderance of and imperfect approach to achieving some level of control of the club is what gives the first half of the book its amazing helium. Ben and Sam clash with the manager who the players generally dislike, but still admire more than Ben and Sam. Navigating through that is quite compelling. It actually is something a reader can look at and think of how it may reflect their own experiences in their industry.

The second half of the book though unravels a bit. For reasons often beyond their control, their team begins to fall apart. This leaves the authors into a great deal of self reflection. The second half winds up taking on a completely different tone and somewhat gets lost in itself. In a way, we learn more about Ben and Sam, but that increased knowledge does not exactly inform us about who they are within the context of running this club. It turns from applied memoir to a more traditional in-the-mind memoir.

If I was to compare it to another work, I would call it a Full Metal Jacket book. Like Full Metal Jacket, the first half is at times stunning and impactful. I read many things that I have actually seen quite similar in the experiences of friends in MLB analytic departments. The second half, like Full Metal Jacket's second half, takes on a different tone and I am a bit nonplussed as to how, as a reader, I am to take it. There certainly are memorable moments in that second half, but it struggles to sustain the energy that continually fuels the first half.

Yes, you should pick this book up. It is one of the best baseball books to come out in the past few years. No, it is not transcendent. It won't make you question your beliefs unless you are one of those data science or die stereotypes that supposedly fill up mothers' basements. It is however a solid and enjoyable case study. There are lessons to be learned, though you might have to figure out what exactly those are on your own.

-----

The Only Rule Is It Has to Work: Our Wild Experiment Building a New Kind of Baseball Team

by Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller

368 pages

Henry Holt and Co.

Before computers were a staple in most homes, I had baseball cards. My favorite ones were not the sought after rookie cards, but those that covered a player's final season and all that came before. Rookie cards mattered if they included minor league seasons. Hours were then spent with my brother "drafting" teams, constructing lineups, piecing together rotations, and arguing which team was superior. We would create model ballparks and discuss differences between playing fields in how they impacted performance. That is what my brother and I did when it rained or snowed or if we were up at 1am and UHF channels were boring.

With that kernel to my being, Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller wrote a book that slots right into the more primordial substrates in my brain. In The Only Rule Is It Has To Work, the duo write about their experience in jockeying into position to run a professional baseball team for a season. No, they were not able to instruct the best players in the World at the MLB stage. Instead, they worked with a rung of very, very good baseball players; the kind that exist on the lower rungs of professional baseball. For a season, they ran baseball operations for the Sonoma Stompers.

While those familiar with the Baseball Prospectus and Five Thirty Eight writings of the two might expect an analytical book, that is not what this is. Yes, the authors underpin their choices with analysis, but that is not the focus. The focus is how exactly do you incorporate these ideas into an organization that would likely benefits from those ideas, but is greatly suspicious of your ability. In other words, this book is primarily a process oriented book about people without industry credibility figuring out how to implement change.

The preponderance of and imperfect approach to achieving some level of control of the club is what gives the first half of the book its amazing helium. Ben and Sam clash with the manager who the players generally dislike, but still admire more than Ben and Sam. Navigating through that is quite compelling. It actually is something a reader can look at and think of how it may reflect their own experiences in their industry.

The second half of the book though unravels a bit. For reasons often beyond their control, their team begins to fall apart. This leaves the authors into a great deal of self reflection. The second half winds up taking on a completely different tone and somewhat gets lost in itself. In a way, we learn more about Ben and Sam, but that increased knowledge does not exactly inform us about who they are within the context of running this club. It turns from applied memoir to a more traditional in-the-mind memoir.

If I was to compare it to another work, I would call it a Full Metal Jacket book. Like Full Metal Jacket, the first half is at times stunning and impactful. I read many things that I have actually seen quite similar in the experiences of friends in MLB analytic departments. The second half, like Full Metal Jacket's second half, takes on a different tone and I am a bit nonplussed as to how, as a reader, I am to take it. There certainly are memorable moments in that second half, but it struggles to sustain the energy that continually fuels the first half.

Yes, you should pick this book up. It is one of the best baseball books to come out in the past few years. No, it is not transcendent. It won't make you question your beliefs unless you are one of those data science or die stereotypes that supposedly fill up mothers' basements. It is however a solid and enjoyable case study. There are lessons to be learned, though you might have to figure out what exactly those are on your own.

-----

The Only Rule Is It Has to Work: Our Wild Experiment Building a New Kind of Baseball Team

by Ben Lindbergh and Sam Miller

368 pages

Henry Holt and Co.

20 May 2016

A Farewell To Jimmy Paredes

On Monday, Roch Kubatko of MASNsports.com broke the news that 27-year-old infielder/DH Jimmy Paredes had been claimed off waivers by the Blue Jays. Kubatko included this quote from O's GM Dan Duquette in a later column.

Sidelined with a wrist injury to start the season, Paredes went 9-for-27 with a homer in a short rehab stint with Norfolk before coming off the DL and forcing a roster crunch that led to Duquette placing him on waivers. As a side note, his last three rehab games were against Buffalo (the Jays' AAA affiliate), so perhaps Toronto's scouts, who are notorious for picking up powerful 1B/DH types off waivers (see Edwin Encarnacion), got a good look and liked what they saw. Maybe he would have cleared waivers had Norfolk not played Buffalo. Who knows.

It's safe to say that the reason Paredes was placed on waivers in the first place was defense. The O's definitely saw the potential in his bat, even during his horrid second half swoon, or else he wouldn't have given him so many at-bats post All-Star break. But with Ryan Flaherty able to provide above average infield glovework off the bench and Hyun Soo Kim forcing his way into more playing time wherever Buck can fit him in, the O's simply didn't have a pressing need for Jimmy Paredes on the team anymore.

This whole thing reminds me a lot of when the Jays put Danny Valencia on waivers last August due to a roster crunch. The A's immediately snapped him up and he has mashed for them since then, going off for a three-homer game just a few days ago. I'm not saying Paredes will suddenly blossom into a 30-homer threat, but there are a few reasons to keep an eye on him as he begins his tenure with Toronto.

The player that Paredes gets compared to the most is Robinson Cano, and looking at his swing you can see why.

The Blue Jays broadcast didn't hesitate to make the comparison in his Toronto debut, and they linked the two by dropping the name of legendary Dominican hitting guru Luis Mercedes, whose claim to fame is shaping Sammy Sosa, and who also currently works with Edwin Encarnacion and...you guessed it, Robinson Cano. According to Jays broadcaster Buck Martinez, Paredes has been working with Mercedes since 2012.

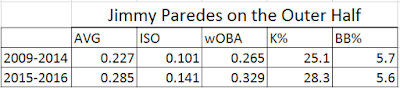

One of Paredes' perennial weaknesses has been his coverage of the outer half. He's always been able to pull inside pitches, but a big key to his mini-breakout in the first half of 2015 was how he was able to handle outside pitches.

Here's a heat map showing his power zones (going by SLG) in the first half of 2015. Paredes took most of his at-bats as a lefty last year, and hit 24 of his 29 extra-base hits as a lefty. Take a look at that big red area outside from the LHB perspective.

He was able to achieve that elite outer-half SLG by taking the ball the opposite way with authority when he needed and generating more flyballs on outside pitches instead of slapping them into the dirt. The stats support this: from 2014 to 2015 his FB% rose by 6%, his Hard% rose by 4%, and his Oppo% rose by 5%.

Here's a GIF of the home run he hit on his very first swing as a Blue Jay.

That looks awfully close to the kind of swings he was taking early in 2015, so either he's a hot starter, or he's beginning to get his outer half power stroke back.

His main woes down the stretch last year stemmed from contact issues. Despite swinging at a higher rate than ever before in 2015, Paredes saw his Contact% drop from 74.8 to 65.6. He was missing pitches inside and outside the zone, and that resulted in a swinging strike rate of almost 20%, which would've led all of baseball by almost three per cent if Parades had enough PA to qualify.

There's no doubt Paredes is a very flawed player, and this post isn't meant to be an attack on the Duquette's decision to let him go. He'll probably continue to be plagued by contact problems, and his power is seriously limited as a righty. But if he can build on the approach he was taking early on in 2015, he could develop into a nice power bat in the homer-friendly Rogers Centre.

"The O's tried but we just didn't find a fit for Jimmy Paredes on this year's team when it was time for him to be reinstated. Jimmy worked hard with us and we appreciate his contributions over the past two seasons."The big switch-hitter showed flashes of promise at the plate over 277 first-half plate appearances in 2015, slashing .299/.332/.475 with 10 homers before falling off a cliff after the All-Star break. Interestingly, his BABIP remained around .370 in the second half, but the power disappeared and his K% shot up from 24.9 to 39.3%.

Sidelined with a wrist injury to start the season, Paredes went 9-for-27 with a homer in a short rehab stint with Norfolk before coming off the DL and forcing a roster crunch that led to Duquette placing him on waivers. As a side note, his last three rehab games were against Buffalo (the Jays' AAA affiliate), so perhaps Toronto's scouts, who are notorious for picking up powerful 1B/DH types off waivers (see Edwin Encarnacion), got a good look and liked what they saw. Maybe he would have cleared waivers had Norfolk not played Buffalo. Who knows.

It's safe to say that the reason Paredes was placed on waivers in the first place was defense. The O's definitely saw the potential in his bat, even during his horrid second half swoon, or else he wouldn't have given him so many at-bats post All-Star break. But with Ryan Flaherty able to provide above average infield glovework off the bench and Hyun Soo Kim forcing his way into more playing time wherever Buck can fit him in, the O's simply didn't have a pressing need for Jimmy Paredes on the team anymore.

This whole thing reminds me a lot of when the Jays put Danny Valencia on waivers last August due to a roster crunch. The A's immediately snapped him up and he has mashed for them since then, going off for a three-homer game just a few days ago. I'm not saying Paredes will suddenly blossom into a 30-homer threat, but there are a few reasons to keep an eye on him as he begins his tenure with Toronto.

The player that Paredes gets compared to the most is Robinson Cano, and looking at his swing you can see why.

The Blue Jays broadcast didn't hesitate to make the comparison in his Toronto debut, and they linked the two by dropping the name of legendary Dominican hitting guru Luis Mercedes, whose claim to fame is shaping Sammy Sosa, and who also currently works with Edwin Encarnacion and...you guessed it, Robinson Cano. According to Jays broadcaster Buck Martinez, Paredes has been working with Mercedes since 2012.

One of Paredes' perennial weaknesses has been his coverage of the outer half. He's always been able to pull inside pitches, but a big key to his mini-breakout in the first half of 2015 was how he was able to handle outside pitches.

Here's a heat map showing his power zones (going by SLG) in the first half of 2015. Paredes took most of his at-bats as a lefty last year, and hit 24 of his 29 extra-base hits as a lefty. Take a look at that big red area outside from the LHB perspective.

He was able to achieve that elite outer-half SLG by taking the ball the opposite way with authority when he needed and generating more flyballs on outside pitches instead of slapping them into the dirt. The stats support this: from 2014 to 2015 his FB% rose by 6%, his Hard% rose by 4%, and his Oppo% rose by 5%.

Here's a GIF of the home run he hit on his very first swing as a Blue Jay.

That looks awfully close to the kind of swings he was taking early in 2015, so either he's a hot starter, or he's beginning to get his outer half power stroke back.

His main woes down the stretch last year stemmed from contact issues. Despite swinging at a higher rate than ever before in 2015, Paredes saw his Contact% drop from 74.8 to 65.6. He was missing pitches inside and outside the zone, and that resulted in a swinging strike rate of almost 20%, which would've led all of baseball by almost three per cent if Parades had enough PA to qualify.

There's no doubt Paredes is a very flawed player, and this post isn't meant to be an attack on the Duquette's decision to let him go. He'll probably continue to be plagued by contact problems, and his power is seriously limited as a righty. But if he can build on the approach he was taking early on in 2015, he could develop into a nice power bat in the homer-friendly Rogers Centre.

19 May 2016

How Good Would Manny Machado Be In An 8 Team League?

Manny Machado has had quite a season so far. He’s always been excellent defensively, but his offensive progression has continued. From 2012-2014, he was just average offensively. But in 2015, he took some real strides as he put up a .286/.359/.502 line for a wRC+ of 134. This year, he has a .333/.387/.653 line with a wRC+ of 181 while playing shortstop. It’s arguable that he’s been the best player in baseball so far. All in all, it’s possible he’s having a better season than Barry Bonds Bryce Harper down in Washington.

All of this got Patrick, Jon and I wondering. It’s pretty clear that Manny is adequate in a thirty team league. How good would he be in a smaller league with only eight teams? Would his performance still be as impressive?

In order to test this, I looked at every players performance from 2013-2016 and determined the best 111 hitters (turns out I included Derek Norris twice on my list) with at least 8 hitters at each position. I also determined the best 48 starting pitchers over this period and 64 relievers. The way I determined the best players over this period consisted of a bit of looking at WAR, a bit of looking at stats like wRC+ and FIP and a bit of using my own judgement. A list of the players I used can be found here (teams were determined largely at random). They probably aren’t perfect, but are close enough.

Next, I determined their wOBA from 2013-2016 against pitchers on this list and pitchers that aren’t on this list. I did this using Pitch f/x data from April-Sept in 2013, 2014 and 2015 as well as 2016 data up until May 13th. This gives me an idea how these batters performed against both the pitching they would face in an eight team league and also how they perform against pitchers that don’t make the cut. The batters that do poorly against the best pitchers likely wouldn’t be successful in a league with eight teams.

Machado has a good, but not great wOBA against the best pitchers in the league at .348. According to Fangraphs’ rule of thumb, this is above average but not great. But he also ranks 94th out of 111 batters on this list. Unsurprisingly, it turns out that it’s difficult to perform well against the best pitchers.

Indeed, there are relatively few batters on this list that are great against the best pitchers. Jose Bautista, Mike Trout, Jose Abreu and Joey Votto all have a wOBA above .370 against these pitchers, but lower than .400. Miguel Cabrera demonstrates why he’s worth the big bucks as he has a .409 wOBA against the best pitchers and .417 against all of the other pitchers. It doesn’t appear to matter whether the pitcher is good or not, because he’ll still crush them.

Other players like Ender Inciarte, Ben Zobrist, Martin Prado and Kevin Kiermaier have below average numbers against the other pitchers but are effective against the best pitchers. This suggests that such batters may do better than expected in an eight team league and may be useful pieces to add for the playoffs.

Also, there are a number of players that do well against bad pitchers, but poorly against the best pitchers. Randal Grichuk and Jackie Bradley Jr. have worse numbers against the best pitchers then Camden Depot favorite David Lough. Mookie Betts has a .393 wOBA against other pitchers, but only a .269 against the best pitchers, suggesting that the Red Sox may want to hold off on a contract extension for him. Dexter Fowler, Baltimore’s favorite villain, has a .380 wOBA against bad pitching (80th out of 111) but only a .280 against good pitching (15th). Bryce Harper has the best numbers in the sample against other pitching (.436 wOBA) but only a .326 wOBA against the best pitching (69th). That’s something to keep in mind the next time the Nationals choke in the playoffs.