The following article is a piece we published in January of last year at one of our old web addresses. As we settle back into our old home here, occasionally we will reintroduce some of those pieces that still have some degree of relevance. The first I want to post is a study I did assessing what would be average value for each position based on 2008 levels of offensive and defensive performance.

January 19, 2009

A player's worth can be defined as the sum of offensive and defensive production. In other words, a player adds to his value by contributing to put runs on the scoreboard and to prevent the other team from scoring. Most work has been accomplished on the offensive side of this equation. This is primarily due to the majority of offense being well characterized by single events, such as a home run or a walk. Defense has been more difficult to analyze as a simple single event requires a good deal of qualification. For instance, a play in the outfield needs to be qualified as to the type of hit (fly ball, line drive, ground ball), where the ball fell, where the fielder started, what is the accepted range for that position, and the resulting effects (as in did a runner tag up or was the batter able to stretch the hit into a double). This requires meticulous analysis and, therefore, most of these methods are proprietary metrics that are often not shared with the general public. The ones that are shared are typically well encapsulated, so the whole process is a black box where you have to trust the statistician. My own transparent method uses the Hardball Times's "balls in zone" data, which entrusts them as knowing what is considered in a fielder's zone.

Recent events have made it obvious that teams are changing the way they evaluate a player's worth. This current offseason, many of have been surprised at how few players were offered arbitration. Pat Burrell made a shade over 14MM last season and now will be earning 16MM total over two seasons in Tampa. This is a bit shocking in that in years past, Burrell would be expected to receive a deal worth about 48MM over 4 years. Now, it seems teams are more strongly considering defense (though the current recession cannot be ignored as a possible contributing factor in the decreasing free agent salaries). An interesting side note in Burrell's worth is that FanGraphs pegs his worth as 11.6MM last year as the Phillies's left fielder. If you shift his position to a full time DH, he was worth 12.5MM, which may show that DHs are currently undervalued in this market. Now, understanding that defense is probably more of a quantifiable contribution toward characterizing the worth of a player, this work aims to determine what levels of offense are required to achieve average production and to present in a quick and easy-to-digest format. For instance, if a left fielder makes 24 less plays than the average left fielder (~20 runs), how well does he have to hit to rate as an average player? How much must his offense compensate for his inability to field relative to his peers? This article will be broken down into two parts. This first segment will focus on the infield and the second will concern itself with the outfield and catcher.

Methods

Offensive Worth

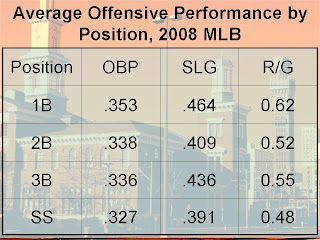

Offensive worth may be calculated in many different ways. For the purpose of this study (which is to develop a quick tool to determine above or below average player worth by position), on base percentage (OBP) and slugging percentage (SLG) will be used within a runs per game formula. It is understood that these are antiquated means to judging a player's worth. For instance, OBP is a generic measurement of out prevention. A walk is not equivalent to a single. A walk is worth about 30-40% less than a single due to a walk having far less probability at scoring a run. A walk though is more predictive of future out prevention than a single can predict. That said, I am ignoring this contention and merely suggesting that OBP and SLG give us a close enough approximate. The "runs per game" formula is as follows: Runs/Game = 1.9*OBP + 1.24*SLG - 0.63. This formula was created using a 2001-2003 data set. Comparing it to 2006-2008, the formula was largely unchanged, so I will keep to the precedent formula in this study. From the equation the average offensive production level was established for each position using the MLB average OBP and SLG data for each position for the 2008 season (Table 1, above). Using this final run value, all paired points in this equation that would equal this run value were determined to illustrate how OBP and SLG can vary and still result in average production for the position. Four other scenarios were run based on the player's defensive ability: 1) prevents 20 runs, prevents 10 runs, gives up 10 runs, and gives up 20 runs. This was accomplished by manipulating the equation to solve for different R/G points based on the scenario. For instance, if a player saved 10 runs per game more than the average player then his bat did not need to account for 0.06 runs per game in order to be considered average.

Results

First Base

The average first baseman contributes the most, offensively, in comparison to the other fielding positions. If he has average aptitude for fielding his position, he generates 0.62 runs per game. In the graph to the left (Figure 1), lines have been drawn to illustrate offensive performance thresholds with respect to fielding ability. First basemen typically fall in between -10 to +10 runs on defense. It is remarkable to see anything beyond those numbers. Adam LaRoche (green dot) would be described as a poor fielder last season. His offensive numbers would be described as average production, but his defense lessens that value. FanGraphs win values (based on more complex formulas than the simple one used here) roughly agrees with this assessment, as they rate LaRoche as being worth 7.7MM based on his playing time, which is less than what the average 1B would be worth -- around 8.6MM. He was still a good value for the Pirates who were paying him 5MM, but this does make one wonder if he will be offered arbitration next year when he has the option to walk. Also shown in the graph is Ryan Howard, a generally average fielder, and Mark Teixeira, one of the premier defensive first basemen in the league. These also seem to agree with the FanGraphs assessment.

Second Base

This position does not require the same level of offensive prowess, as athleticism and refined motor coordination is required at second. The number of people who can actually play second reduces the population at large and, therefore, you will find fewer mashers here than at less skilled defensive positions. You will note that Chase Utley is off the charts with his performance last year (Figure 2). He made about 25 plays more than the average second baseman and had offensive potential that is rarely seen in a second baseman. It was truly an impressive season. Hopefully, his hip injury does not impair him too much. If it does, he has a great deal of buffer until he becomes an average baseball player. If the injury takes only his defense, his bat easily plays at first. Orlando Hudson is a free agent with Type A compensation attached. He still profiles as an above-average second baseman primarily due to his bat. Unfortunately, his defense has been regressing for the past four seasons. As age declines go, this is expected for a second baseman. The question is whether his bat will hold up. Offensive declines for this position are typically quite rapid and occur around ages 33-34. A team in need of a second baseman probably could use him for a year or two, but the cost of a draft pick be deterring some. An offhand note, if Roberts was on the chart, he would be just above Hudson and linked to the average defensive line. He was worth about a win more than Hudson. Finally, Robinson Cano is also shown and, given the benefit of the doubt, deemed as an average defender. We concur with FanGraphs and think that he was one of the worst second basemen in baseball last season.

Third Base

Defensive production range at third is similar to first base in that it typically spans about -10 runs to +10 runs. In the graph we have one of the best defensive third basemen in Adrian Beltre, an average one in Alex Rodriguez (Melvin Mora would qualify as this last year), and a poor fielding option with Garrett Atkins (Figure 3). As much as the Mariners are hammered for their signing of Beltre, he has actually been a good acquisition producing more value than what he costs and will probably have a Type A designation on him with arbitration offered next off season. That is a free agency rarity. The graph also explains why Garrett Atkins has been dangled about and may not be offered arbitration when his time comes. Ian Stewart is projected to have a better bat and a better glove at third. Alex Rodriguez is also shown and, to no surprise, he is not in any immediate danger of being one of the Yankees aged albatrosses. Again, our results are not wildly different from the FanGraphs assessment.

Short Stop

This infield position requires the least amount of offensive production. The three fielders chosen as examples here are Cesar Izturis (very good), Jose Reyes (average), and Stephen Drew (poor) (Figure 4). A player with Izturis's glove needs to produce an OPS of about 665. That appears to be out of his ability as a hitter. Still, to receive SS production -10 runs below average for 2.4MM next year is quite cost efficient. Stephen Drew's position may be a bit cumbersome. He is having difficulty sticking at shortstop and his 2007 season at the plate was horrible. If he can continue hitting like he did last year, he will be valuable. That might be a big if considering his performance was largely related to his batting average. Time will tell. We still find solid agreement with FanGraphs.

Part II

The second part of this article will post Wednesday. As mentioned earlier, it will focus on the outfield and catcher.

2 comments:

I'm having a bit of a difficult time interpreting the graphs. Are you saying that, in order for a +20 runs defender (blue line) to be an average player, this is the line along which he must perform offensively? Thus, when you take an average defender (say, Ryan Howard) and plot his SLG, OBP you can see his contribution relative to an average player at his position (the black line)?

The line represents the break even mark for offense depending on your defense.

Post a Comment