So, what happened? First and most obviously, Trumbo's home run power from 2016 evaporated. 47 home runs was always going to be difficult to replicate, but a lot was made of Trumbo's supposed launch angle changes that took him from being a good power hitter to a great one. In an age in which launch angles have become a major focus for a lot of hitters, this made sense and tracked with the idea that Trumbo always had elite power but didn't take enough advantage of it. The problem, here, is that the only thing that really changed in 2016 was Trumbo's home run output. By measures like fWAR and WRC+, Trumbo had one of the least productive 40 homer seasons ever. This doesn't mean he was bad, of course, but it does show that, aside from the homers, Trumbo just didn't do much of anything else better than he'd done in the past. Consider:

Career BABIP: .288

2016 BABIP: .278

Career K Rate: 24.8%

2016 K Rate: 25.5%

Career BB Rate: 6.8%

2016 BB Rate: 7.6%

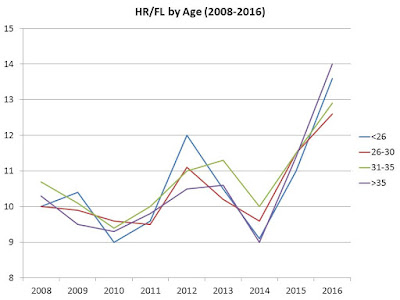

You get the idea. The one thing that did change was Trumbo's home run to fly ball rate. A ridiculous 24.6% of Trumbo's fly balls resulted in home runs, up from a career norm of just over 18%. This essentially explains the difference between Trumbo's 2016 and the rest of his career. This season, that number is all the way down to 14%, accounting for the worst isolated power and slugging percentage numbers in his career. Other than that? Things really don't look that much different. He's hitting the ball somewhat less hard than last season but is not significantly off from his career average, and his walk and strikeout rates are both better than his career.

The second thing that's happened is likely related to the first, and it's his dramatic decline in ability to handle inside pitches. The heat maps below are from 2016 and 2017, and we can clearly see that Trumbo demolished inside pitches last year but has struggled mightily this season.

The differences are stark. Trumbo has been able to effectively handle pitches on the outer half of the plate this season, but simply hasn't been able to turn on the inside pitch like he did in 2016. Worryingly, this looks similar to his career worst year of 2014.

Trumbo has been a bit better of late, posting an .806 OPS since the latter part of August, but even then has only hit a couple of homers. Perhaps he will buck his normal trend of having poor second halves and save his season in September, but there's still the issue of Trumbo being owed over $25 million over the next two seasons. It's fair to wonder what the Orioles saw to reward him with a relatively lavish deal, especially given that power hitters with no defensive value went extremely cheaply last off season. One has to wonder what the Orioles lineup could have looked like with a Mancini/Pedro Alvarez/other cheap lefty bat platoon situation at DH that would have cost about 1/10 of Trumbo's overall deal.

The contract was not a massive overpay at the time, but given that Trumbo is having (at best) a replacement level season means it is going to be difficult for him to live up to even a modest deal at this point. With Mancini establishing himself as a legitimate big league hitter and Chris Davis not going anywhere, the O's are somewhat stuck. It's hard to imagine that Trumbo has much trade value, and he's clearly making too much money to release or move into a part time role. At the worst, he can serve as a cautionary tale (because Bud Norris and Travis Snider didn't, apparently) about the pitfalls of paying for career years. At best, maybe he rediscovers some of that fly ball magic and powers the O's to another playoff appearance.