I have been asked to write on this by a few of my readers as I tend to write about scientific matters in baseball and this sort of thing speaks to my training. My research at the UMD-B's Medical School was focused on reproduction and DNA damage, but my class room training was a bit broader. This should clue you in on my perspective in that how I typically see things differently than a medical doctor. The best way I can explain it is that from my experience a medical doctor acts more as an advocate for the patient than as a strict scientist. This means that they tend to believe in the benefit of procedures before the science can weigh in on the matter.

Another comparison is the PED issue in baseball. There are the advocates (e.g. players, gym rats) and the science. Sometimes the advocates get ahead on a specific issue, such as steroids improving athletic performance. When the advocates get ahead of the curve though, they tend not to fully understand the procedure and can misapply it. Thus, a poorly understood application of steroids could result in worse performances. There is actually still much debate as to how effective steroids were for hitters generating power as well as other purported usage. There is still misinformation out there as to how steroids affects head size and eye sight. Science has largely caught up with this treatment and how to effectively use it in a clinical setting, but that often poorly translates as the message is transcribed into the gym locker room.

I do not see myself as an advocate. You probably already know this from my previous writings on PEDs. I like to see solid proof of something working. This means getting into the nuts and bolts, understanding the science with a critical view. After a quick overview, I will delve into some more recent journal articles.

Although summarized in Britt's and Andrew's articles, I think it might be beneficial to actually see an application of PRP. In the video below, a physician uses the treatment for a patient with tendinitis in the elbow. Tendinitis is an acute injury to the tendon that is accompanied by inflammation.

Platelet-Rich Plasma Augmentation for Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

Castricini et al. AJSM

One thought about the slow healing process with any sort of tendon tear is that the tissue is poorly vasculated. In other words, little blood is getting to the area. Blood carries all sorts of proteins and other chemicals that aid in the healing process. The hypothesis is then that by concentrating the components of the blood largely responsible for healing (e.g., insulin growth factor, thrombin) and then applying them to the surgical site that it would then result is greater healing.

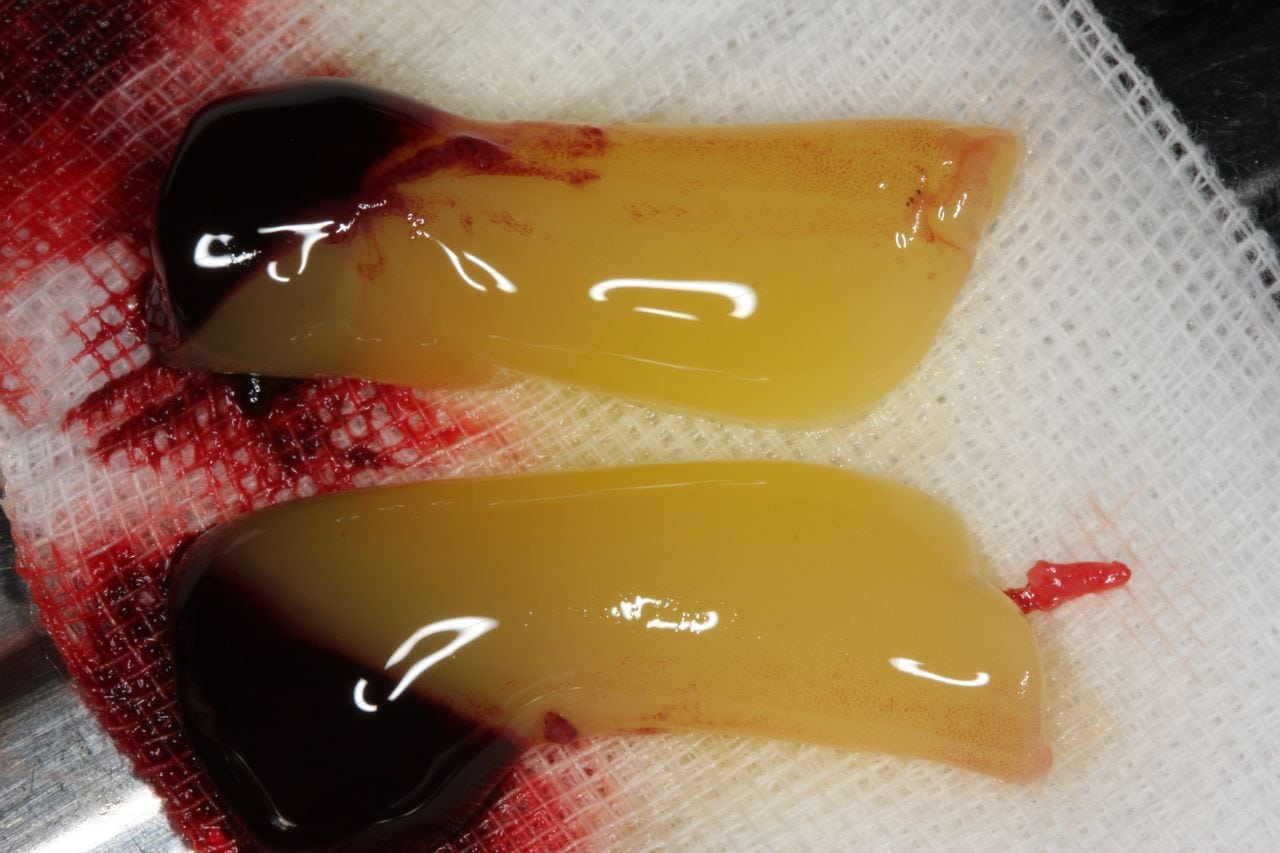

In this study, they are not looking at cases similar to Zach Britton's. They are looking at tears that required surgery. In this study, 88 patients were included with 45 given PRP in the form of a fibrin matrix. Basically, you use a polymerized fibrin matrix so that you are able to physically connect it to the repaired area. This is different from Britton's treatment where his PFP is not in a fibrin matrix and is instead directly injected at the site of inflammation. The PRFM look like this:

Again, Britton does not fit in any of these categories.

Growth Factor-based Therapies Provide Additional Benefit Beyond Physical Therapy in Resistant Elbow Tendinopathy

Creaney et al. 2011 BJSM

This article focuses on patients who have not found any success with traditional physical therapy techniques to heal their elbows. The researchers decided to compare PRP with ABI. PRP again is the injection of concentrated platelets and growth factors while ABI is whole blood injection. There was no control, placebo control, or comparison to a well known technique, such as administration of cortisone. The researchers felt it was not ethical to have a group in the study that would not receive any treatment. They found that both PRP and ABI produced similar results. They both had a success rate around 70% (success defined as improvement in a Tennis Elbow Evaluation metric) over the course of six months (injection was at 0 and 1 month). This looks like a solid result, but it hurts not having a control or traditional treatment comparison.

Conclusion

One of the first rules in treating someone is to do no harm. This is where I divide PRP from something like hGH. I have a difficult time seeing how currently applications of PRP could be dangerous to the patient. I think there is also some data out there that suggests that PRP might be of some use to the healing process. There are issues with knowing whether or not it works or how to use it best. For instance:

- No information on the level of concentration that is important for creating the PRP fraction,

- No observations of the mechanisms of action for this treatment,

- Few randomized studies and the existing randomized studies do not show a clear benefit, and

- No consensus on injection site or frequency.

It might work for Britton, it might not. We really do not know. If he gets betters, it does not mean it worked. If he gets worse, it does not mean it didn't work.

No comments:

Post a Comment