Mark Reynolds had a very good year at the plate. He hit 37 home runs, helping himself to a .483 slugging percentage and he walked 12.1% of the time that counteracted his low batting average. It was in fact his second best offensive year in his career worth about 31 runs over a replacement third baseman. However, his defense nearly negated his offensive worth.

Defensive Metric 1B (375.2 inn) 3B (984.1 inn) proj 3B (1360 inn)

UZR -5.3 runs -22.8 runs -31.5 runs

Total Zone -6 -18 -25

DRS -4 -29 -40

I typically like to have about 3000 innings to determine how well a player performs at an infield position. If you include his season last year, you will wind up with about -15 to -20 runs. Reynolds at his best provides about 30 runs above replacement level and with that level of defensive ineptitude, it is difficult to match what is passable for an average player (+20 runs above replacement).

However, the Orioles have the ability to make him a more valuable player. By switching him to another position, his glove may not be as much of a hindrance on the team. The Orioles did that by playing Reynolds at first base about 30% of the time. With time, I think it is not unthinkable that Reynolds could be an average first baseman defensively. That alone would save the team three wins assuming that his replacement at third base is average defensively and provides the same offense from first base that Reynolds in replacing (Derrek Lee's 706 OPS).

A shift to first base and maintaining his offensive production does not make Mark Reynolds a 3.1 WAR player because it is far easier to find offensive production at first than it is at third. Due to this shift in expected offensive production for a replacement player, Reynolds' worth would actually be 1.8 wins above replacement, 1.3 wins less than if he was at third. If you put him in as a DH, that value is 1.2 wins above replacement. As a 3B, 1B, or DH, Reynolds is not an average player (~2 wins above replacement).

Reynolds would rate as an average or above player if he was capable of playing an average left field. He has played three innings in the Majors, twenty three games in the Minors, and, as far as I can tell, he did not log any notable time in the outfield during college. Reynolds should have the tools to play left field though. He has good speed for a big man. He has swiped over twenty bases during a season and collects a couple triples every year. He also has a strong arm. Although he has not logged any significant time out there, I think it could be a position he could handle. In that case, he would be worth 2.3 wins above replacement. These numbers should not be treated as guarantees, but the take home point is that Reynolds likely has a better chance of being useful as a LF than as a 1B, 3B, or DH.

Of course, these values rely on an abstract situation. A major issue is to figure out who exactly would be playing at 1B, 3B, LF, and DH. I will go through a few options for each position and then can determine which would be the best mix.

1B

Reynolds (1.8 WAR; 7.5 MM), Prince Fielder (5.0; 20),

Chris Davis (0.5; 0.4), Carlos Pena (2.6; 10)

3B

Reynolds (0.3 WAR; 7.5 MM), Aramis Ramirez (2.5; 15),

Robert Andino (1.0; 1), Marco Scutaro (2.8; 6)

DH

Reynolds (1.2 WAR; 7.5 MM), Jason Kubel (1.5; 5),

Luke Scott (2.0; 6.4), Nolan Reimold (1.2; 0.5)

LF

Reynolds (2.3 WAR; 7.5 MM), Michael Cuddyer (2.5; 10),

Scott (2.6; 6.4), Reimold (1.8; 0.5)

It is easy to see that if Marco Scutaro makes it to free agency, that he might be best suited for the Orioles. There is doubt that the Red Sox will tender him a contract. It might make sense to offer them something in a deal for him. Scutaro actually has a decent amount of worth and has experience at third base. The rest is a bit of mix and match. The most reasonable set up would be to have Reynolds in left and Pena at first with Scott and Reimold working with the DH spot and Reimold backing up left and right field. Adding Fielder in lieu of Pena, gives the team 2-3 more wins.

The most accomplished squad would deliver about 12 WAR. Last year, the O's managed approximately 0.7 WAR total from those positions. You read that right. This team can go from a high 60s team to a low 80s team by merely adding Prince Fielder and Marco Scutaro in place of Derrek Lee and Mark Reynolds, shifting players around, and Scott getting healthy.

That is stunning to me.

30 September 2011

28 September 2011

Expanded Roster: MacPhail's Arms

During the month of September, Camden Depot expanded the rosters beyond Nick Faleris and Jon Shepherd. This enabled our audience to speak directly outside of the comment box as well as shine a light on other Orioles writers. The final article is from Will Beaudouin. Ben Feldman and Kevin Williams wrote pieces. I would like to thank everyone who submitted pieces. They all made me think and consider new ideas or new ways of presenting old ideas. However, we limited space we had to select the three best. Also, congratulations to Kevin Williams whose piece was also publicized on our home ESPN MLB site in a Sweet Spot article. Thanks again and we might look into this again when Spring Training comes around.

MacPhail's Arms

by Will Beaudoin

|

| MacPhail's first arm - Rocky Cherry |

If the reports and rumors that have surfaced in recent weeks are to be believed, Andy MacPhail’s tenure as President of Baseball Operations will soon come to an end. MacPhail, first hired in June of 2007, is well known for having preached his oft-repeated mantra of “grow the arms and buy the bats” as well as his claims that the Orioles needed to acquire more “pitching inventory”. At face value it seemed that MacPhail desired to accumulate enough quality organizational pitching depth in order to prevent the Paul Shuey’s of the world from being called upon when ranks inevitably thinned.

The objective of this piece is to look back at the pitching inventory acquired during the MacPhail era and evaluate said inventories potential moving forward. Starting in June of 2007 through the present day, I’ve compiled a list of every pitcher acquired by MacPhail who’s pitched thirty or more major league innings as an Oriole. For the sake of simplicity I’ll be using Fangraphs’ fWAR to quantify value. This isn’t a cost-benefit analysis—salaries will be ignored for this exercise. Many of the pitchers who didn’t pan out were smart pickups at the time of their acquisition and vice versa. I simply want to look at the raw value these pitchers brought to the club during their time in Baltimore.

Note: Players are listed under the first year they were acquired starting June 20th, 2007. Innings pitched and fWAR totals are their Oriole career numbers. Players subsequently reacquired (e.g. Hendrickson, Uehara) are only listed the first year they were acquired. [edit - The end date for the fWAR time frame is September 6th, 2011].

2007 Regular Season Acquisitions

- Rocky Cherry: 33.1 IP, fWAR -.7

- Fernando Cabrera: 38.1 IP, -.6 fWAR

07/08 Offseason/Regular Season Acquisitions

- George Sherrill: 95 IP, 1.4 fWAR

- Chris Tillman: 180.2 IP, .7 fWAR

- Brian Matusz: 262 IP, 2.9 fWAR

- Brian Bass: 107.1 IP, .1 fWAR

- Lance Cormier: 71.2 IP, .7 fWAR

- Alberto Castillo: 48.2 IP, -.1 fWAR

- Matt Albers: 191.2 IP, 1.3 fWAR

- Dennis Sarfate: 102.2 IP, .2 fWAR

- Randor Bierd: 26.2 IP, .1 fWAR

- Steve Trachsel: 39.2 IP, .1 fWAR

- Alfredo Simon: 156 IP, -.1 fWAR

08/09 Offseason/Regular Season Acquisitions

- Mark Hendrickson: 191.1 IP, 1 fWAR

- Koji Uehara: 216 IP, 4.2 fWAR

- Rich Hill: 57.2 IP, .4 fWAR

- Adam Eaton: 41 IP, 0 fWAR

- Cla Meredith: 43.2 IP, -.3 fWAR

09/10 Offseason/Regular Season Acquisitions

- Mike Gonzalez: 48 IP, .8 fWAR

- Will Ohman: 30 IP, .1 fWAR

- Kevin Millwood: 190.2 IP, 1.3 fWAR

10/11 Offseason/Regular Season Acquisitions To Date

- Chris Jakubauskas: 67.2 IP, .2 fWAR

- Tommy Hunter: 37.2 IP, .4 fWAR

- Jeremy Accardo: 32.1 IP, -.2 fWAR

- Kevin Gregg: 52 IP, -.4 fWAR

TOTAL: 25 pitchers acquired (30 IP minimum), 2,371.2 Total IP, 12.7 Total fWAR

Before any substantial analysis, a few disclaimers: I realize assigning sole responsibility for performance of these players to Andy MacPhail is foolish. It’s impossible to know how many he specifically targeted, how many were suggested by his staff, etc. I also realize that there’s a very strong argument against attributing Matusz to MacPhail. I agree that Joe Jordan should receive the credit for drafting Brian and bringing him into the organization, but considering the scope of this analysis I think it’s fair to include him. Finally, many of these players have a chance to contribute to the organization in the future. Chris Tillman could still put it together and live up to his potential. If this happens, MacPhail will be the one to thank. I’m not trying to assign a final grade to every acquisition.

Brief Observations

Over the course of his four and a half years in the organization, MacPhail brought in roughly 2.8 pitching wins a year and roughly half a win for every transaction made.

Seventeen of the listed players were predominantly relievers while only eight were predominantly starters

Of the twenty-five players listed, only six have been worth one win or more: Sherrill, Matusz, Albers, Uehara, Hendrickson and Millwood. Of these six only Uehara and Hendrickson were acquired through free agency and only Millwood and Matusz were starters.

Eight players have had a negative total value: Rocky Cherry, Fernando Cabrera, Alberto Castillo, Steve Trachsel, Cla Meradith, Jeremy Accardo, and Kevin Gregg. Together these players have been worth a total of -3.1 wins.

Conclusion

The fact that only 12.7 wins were brought in over the course of four and a half year is astounding. The pitching staffs of the Rays, Red Sox, and Yankees have all been worth more than twelve wins this year alone. Taken with the fact that the Orioles were ranked 21st in staff fWAR at the end of 2007—MacPhail’s first half season—it becomes obvious why the Orioles have been so poor in recent years.

It’s obvious that MacPhail wanted a homegrown pitching staff, but when that plan failed (or faltered if you’re optimistic) there was no plan B. When Tillman struggled there was no promising prospect behind him to take his place. The same could be said of Matusz this year. MacPhail pinned the hope of the organization onto a handful of top pitching prospects and seemingly stopped accumulating any meaningful talent beyond that. While other organizations have more pitching prospects than spots in the rotation to fill the Orioles have experienced the exact opposite.

Moving forward, of the twenty-five pitchers listed, only Hunter, Matusz, and Tillman could be considered possible pieces for the future. The minors are barren in the upper levels as well. Where is the next wave of reinforcements coming from? Obviously MacPhail has had his share of bad luck, but for a man whose goal was to acquire “inventory” there’s relatively little to show for it throughout the entire organization. There are other promising arms acquired before MacPhail, of course. I hold out hope that a fully healthy Jake Arrieta can be an effective pitcher while Zach Britton’s up and down season has me excited about his future potential. But even when you take Arrieta and Britton into consideration you’re left with five potential long-term pieces and four spots empty in the rotation. Unless the Orioles get extremely lucky that’s not going to cut it. Building a pitching staff is a game of attrition, and as they’ve been in years past, the organization under MacPhail was once again ill-adept to deal with this reality.

26 September 2011

Matusz actually did not have the worst season ever.

|

| Steve Blass |

That is a horrible season. There are probably about 200,000 seasons on record for a starting pitcher with 10 starts and 40 innings, so scoring in the 0.03 percentile is bad enough without resorting to a misguided statistic like ERA. It should be noted that Matusz had a long way to go before he assumed the worst rWAR ever for a pitcher. The worst season is Steve Blass at -5.8 rWAR. Matusz would have needed 112 innings pitched to have achieved what Blass did. Blass accomplished his feat in 88.2 innings. Matusz was bad, but he was not Steve Blass bad.

Using the 200 worst rWAR seasons on record for starting pitchers, I created a rWAR-A by divided rWAR by innings pitched and multiplying that by nine. By turning it into a rate statistic, we can normalize pitching opportunity and hopefully put all of these pitchers on equal footing. The following are the worst seasons for a pitching according to this rate (min 10 games and 40 innings pitched):

1. Steve Blass 1973 -0.592

2. Andy Larkin 1998 -0.558

3. Brian Matusz 2011 -0.476

4. Luis Mendoza 2008 -0.442

5. Micah Bowie 1999 -0.441

6. Roy Halladay 2000 -0.429

7. Cal McLish 1944 -0.407

8. Dick Conger 1943 -0.365

9. Tony Kaufman 1927 -0.362

10. Hideo Nomo 2004 -0.343

Other Orioles

63. Dave Johnson 1991 -0.214

111. Jeff Ballard 1991 -0.168

151. Jack Fisher 1962 -0.130

160. Dennis Martinez 1983 -0.124

What we can take home from this is that we have witnessed one of the worst seasons on record for a pitcher, but, alas, not the worst. Rough year for Matusz. I hope he gets himself back on track.

25 September 2011

CDOBC: But Didn't We Have Fun? Chapter 5

For more about the book club and books on the agenda click here.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13

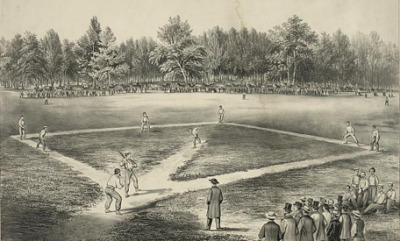

Chapter 5: Balls, Bats, Bases, and the Playing Field

This is a great chapter. If you ever find yourself in a library waiting for your significant other to find an audiobook she would like for her commute, you will likely have enough time to sit and make your way through these pages. As cleanly summarized in the title, it is a brief description of the types of balls, bats, bases, and playing fields that were in use in baseball during this period in the mid-1800s. As shown before, the simple rules that the Knickerbockers' devised and dispersed standardized many aspects of the game, but left many open for interpretation. For a single team or field, this makes complete sense as selection of ball, bat, bases, and field are largely without choice or can be quickly determined and followed from there on out. However, if two different populations of ball players never much interacted then you are likely to have two wildly different implements for your game.

Two major extremes are present in this chapter. In one locale, I believe Michigan, the version of baseball played there was with a 10 inch diameter baseball whose core was a melted down rubber shoe with yarn tied around it and leather keeping it together. They had one ball and it was highly treasured (in fact, it was common during this time that when a team won a game, the winners were awarded with a baseball). On the other end was a group of rural folk who supposedly wrapped twine around a bullet to form a small little ball that injured many a player's hands. As you can imagine, these two games would be played in vastly different ways and players accustomed to one would be at a significant disadvantage to play it a different way.

The use of a harder ball often resulted in a more destructive projectile. Where the town ball game could be played in the commons, town square, or on a vacant sand lot, the new baseball game was wont to break windows and terrorize residents. One part of the book that stuck close to one of my own experiences is from a first hand account of a ball player who was kicked out of his town square because an elderly gentleman was concerned about them hitting balls into the trees, knocking down branches, and potentially killing the trees. The same thing happened to me in a park near Capitol South where my softball team captain this past summer had us practice in a small park with dogs, babies, and people playing boche ball running around. An elderly man walked up to us and said the same thing. I was actually quite glad that no one got hurt as there was no good reason why we were out there. I felt at one with those 1850's ball players.

Anyway, the transition resulted in many more towns and cities to ban all ball playing within their limits. Many compromises began coming into play as many clubs began using dead balls to keep them closer to the confines of the city. The 10 inch diameter ball with a seven inch chunk of rubber in the middle was discarded for one with less rubber and more yarn. "Bullet balls" and other small projectile were being replaced by larger balls that traveled less distance. It is actually amazing to think how often during this time the types of balls changed whereas in MLB there appears to be only four or five changes to the ball in the past five years (with most of them being completely unintentional). Very different.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13

| "Lemon Peel" baseball |

This is a great chapter. If you ever find yourself in a library waiting for your significant other to find an audiobook she would like for her commute, you will likely have enough time to sit and make your way through these pages. As cleanly summarized in the title, it is a brief description of the types of balls, bats, bases, and playing fields that were in use in baseball during this period in the mid-1800s. As shown before, the simple rules that the Knickerbockers' devised and dispersed standardized many aspects of the game, but left many open for interpretation. For a single team or field, this makes complete sense as selection of ball, bat, bases, and field are largely without choice or can be quickly determined and followed from there on out. However, if two different populations of ball players never much interacted then you are likely to have two wildly different implements for your game.

Two major extremes are present in this chapter. In one locale, I believe Michigan, the version of baseball played there was with a 10 inch diameter baseball whose core was a melted down rubber shoe with yarn tied around it and leather keeping it together. They had one ball and it was highly treasured (in fact, it was common during this time that when a team won a game, the winners were awarded with a baseball). On the other end was a group of rural folk who supposedly wrapped twine around a bullet to form a small little ball that injured many a player's hands. As you can imagine, these two games would be played in vastly different ways and players accustomed to one would be at a significant disadvantage to play it a different way.

The use of a harder ball often resulted in a more destructive projectile. Where the town ball game could be played in the commons, town square, or on a vacant sand lot, the new baseball game was wont to break windows and terrorize residents. One part of the book that stuck close to one of my own experiences is from a first hand account of a ball player who was kicked out of his town square because an elderly gentleman was concerned about them hitting balls into the trees, knocking down branches, and potentially killing the trees. The same thing happened to me in a park near Capitol South where my softball team captain this past summer had us practice in a small park with dogs, babies, and people playing boche ball running around. An elderly man walked up to us and said the same thing. I was actually quite glad that no one got hurt as there was no good reason why we were out there. I felt at one with those 1850's ball players.

Anyway, the transition resulted in many more towns and cities to ban all ball playing within their limits. Many compromises began coming into play as many clubs began using dead balls to keep them closer to the confines of the city. The 10 inch diameter ball with a seven inch chunk of rubber in the middle was discarded for one with less rubber and more yarn. "Bullet balls" and other small projectile were being replaced by larger balls that traveled less distance. It is actually amazing to think how often during this time the types of balls changed whereas in MLB there appears to be only four or five changes to the ball in the past five years (with most of them being completely unintentional). Very different.

CDOBC: But Didn't We Have Fun? Chapter 4

For more about the book club and books on the agenda click here.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13

Chapter 4: How the Game was Played

As peculiar and momentous as it was to write down rules to a simple game, perhaps more interesting is how the rest of the game was played. In today's environment, the rule book is dense. What started as one sheet of paper has grown into a 130 page document. This is also not entirely correct as the original rule book also included items that would eventually evolve into aspects of the collective bargaining agreement (CBA). The CBA is 241 pages in length. There are also a plethora of other documents that ownership uses to self-regulate, players use to self-regulate, umpires use to self-regulate, an MLB agreement with umpires, teams use to self-regulate, and so on and so on. So, it could be seen that that single page has become a few thousands pages of rules and regulation. What spurned that growth was what caused those initial rules to be put into place: arguments getting in the way of the game.

Perhaps one of the more interesting parts of the early regulation of the game was the role of umpires. Umpires were usually seated thirty feet from the plate under an umbrella with drink and food at his disposal. They did not call balls or strikes (as there were no called pitches). They never actively engaged themselves into the game. Instead, they were largely ceremonious and were only involved in the game when there was a close play and the player yelled for a "judgement." Typically, the umpire was a well known individual and a pillar of the community. The umpire typically knew very little about the game. His role was to make sure the spirit of fair play was maintained and that all participants were to remain gentlemanly in conduct.

A primary problem with this was that baseball was as much about winning as it was about having "fun." Such a situation means that players began doing what they could to win without appearing to cross the line of being a gentleman. One problem occurred as the conversion from rocks, stumps, and stakes to sand or sawdust bag bases occurred. This combined with the emergence of better kept fields resulted in the strategy of sliding to decelerate quickly as well as to avoid a tag. Crowds were often surprised by this technique and often assumed a player stumbled, rolled, and fortuitously avoided a tag. Blowback against this technique and the way fields were maintained kept this to a minimum until professionalism occurred.

A second, and more prominent, issue was that pitchers were beginning to establish themselves as one of the more important defenders. There were no called pitches, but pitchers would try to get batters to swing at bad pitches and not hit the ball so solidly. In response to this, batters would merely wait until they found a pitch to their liking. It was not unheard of for single innings to involve a hundred pitches. Obviously, this would likely make the play less interesting as crowds would sit and wait for a dozen or so pitches before a batter would swing. This largely took the umpire off his pampered life and into the fray behind the catcher for pitches to be called.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13

Chapter 4: How the Game was Played

As peculiar and momentous as it was to write down rules to a simple game, perhaps more interesting is how the rest of the game was played. In today's environment, the rule book is dense. What started as one sheet of paper has grown into a 130 page document. This is also not entirely correct as the original rule book also included items that would eventually evolve into aspects of the collective bargaining agreement (CBA). The CBA is 241 pages in length. There are also a plethora of other documents that ownership uses to self-regulate, players use to self-regulate, umpires use to self-regulate, an MLB agreement with umpires, teams use to self-regulate, and so on and so on. So, it could be seen that that single page has become a few thousands pages of rules and regulation. What spurned that growth was what caused those initial rules to be put into place: arguments getting in the way of the game.

Perhaps one of the more interesting parts of the early regulation of the game was the role of umpires. Umpires were usually seated thirty feet from the plate under an umbrella with drink and food at his disposal. They did not call balls or strikes (as there were no called pitches). They never actively engaged themselves into the game. Instead, they were largely ceremonious and were only involved in the game when there was a close play and the player yelled for a "judgement." Typically, the umpire was a well known individual and a pillar of the community. The umpire typically knew very little about the game. His role was to make sure the spirit of fair play was maintained and that all participants were to remain gentlemanly in conduct.

A primary problem with this was that baseball was as much about winning as it was about having "fun." Such a situation means that players began doing what they could to win without appearing to cross the line of being a gentleman. One problem occurred as the conversion from rocks, stumps, and stakes to sand or sawdust bag bases occurred. This combined with the emergence of better kept fields resulted in the strategy of sliding to decelerate quickly as well as to avoid a tag. Crowds were often surprised by this technique and often assumed a player stumbled, rolled, and fortuitously avoided a tag. Blowback against this technique and the way fields were maintained kept this to a minimum until professionalism occurred.

A second, and more prominent, issue was that pitchers were beginning to establish themselves as one of the more important defenders. There were no called pitches, but pitchers would try to get batters to swing at bad pitches and not hit the ball so solidly. In response to this, batters would merely wait until they found a pitch to their liking. It was not unheard of for single innings to involve a hundred pitches. Obviously, this would likely make the play less interesting as crowds would sit and wait for a dozen or so pitches before a batter would swing. This largely took the umpire off his pampered life and into the fray behind the catcher for pitches to be called.

CDOBC: But Didn't We Have Fun? Chapter 3

For more about the book club and books on the agenda click here.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | App 1

Chapter 3: The New York Game Becomes America's Game

One of the major reasons why the Knickerbocker's style of play grew beyond their influence on the Burroughs was the transition between centralized news and the telegraph. On December 6, 1856, the newspaper Porter's Spirit of the Times printed the Knickerbocker rules. Oral transmission of the rules of the game limited how far the game could travel and how accurate the transmission of these rules would be. By using print, the rules could be effectively communicated by the letter. News at this point was beginning to be decentralized from Washington and New York with the development of the telegraph system, allowing newspapers in Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, etc. to have first hand accounts with their own perspective as well as being able to join news associations who would offer stories for print. This period of transition allowed for the exact Knickerbocker rules to spread across the country. The aura of New York sophistication could be helpful to ball players who were maligned for spending time playing a children's game. If you can point to New York and say this is played there, it gives you more credibility.

However, technological achievements and a country still somewhat looking to the East Coast for instruction were not alone in spreading the game. These things help convince people to try a game that is played in New York City as their was certainly respect for a perceived sophistication back east, but it would not make people continue playing the game. It had to be enjoyable as well.

I touched on it slightly in the last chapter review, but I think the spread primarily had to do with this: no soaking, foul balls, and what became the use of a harder ball. With the elimination of soaking, there was no longer a need for a fairly soft ball. No longer worried about injuring a person with a hard one, they could use balls that could travel a greater distance. This is important because there was no longer foul territory. The field would be too collapse with a short distance ball, a harder ball extended the field of play. This meant that you no longer had to be a lean, athletic, and fast person to be able to play. The importance of power and speed became far more balanced.

By balancing power and speed, it enabled a few things that make the game enjoyable. First of all, it increased the population able to play the game. People with body types that are not especially suited for chasing down runners and then soaking them were not well suited for the town ball games. Baseball enabled them to hit the ball far to avoid being chased down as well as allowed them to use their arm to throw at the bases which required less skill than throwing at a moving target. Second, I think it made baseball more enjoyable for spectators. Town ball was a spectacle of players hitting the ball in front of and behind home plate, often intentionally glancing batted balls to go no further than 50 feet. The idea was often just to get to first and successfully get to bases in run downs. If one chose to hit the ball well, it would go about 120 to 150 feet. Town ball was essentially a series of guys chasing each other and hitting them with balls. The Knickerbocker rules lengthen the field and the fans largely enjoyed the long ball. Everyone seems to love a good feat of strength.

What I find interesting is how a major current discussion in baseball is the relative worth of a game relying on good pitching versus good hitting. That is where we are now. Back then, it was about good fielding versus good hitting. Pitchers were considered merely one of the nine fielders. The spirit of the rules primarily limited a pitcher back then to merely serve up balls for batters to hit and fielders to field. Over the next few chapters we are bound to see the development of pitchers changing their own role.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | App 1

Chapter 3: The New York Game Becomes America's Game

One of the major reasons why the Knickerbocker's style of play grew beyond their influence on the Burroughs was the transition between centralized news and the telegraph. On December 6, 1856, the newspaper Porter's Spirit of the Times printed the Knickerbocker rules. Oral transmission of the rules of the game limited how far the game could travel and how accurate the transmission of these rules would be. By using print, the rules could be effectively communicated by the letter. News at this point was beginning to be decentralized from Washington and New York with the development of the telegraph system, allowing newspapers in Boston, Chicago, St. Louis, etc. to have first hand accounts with their own perspective as well as being able to join news associations who would offer stories for print. This period of transition allowed for the exact Knickerbocker rules to spread across the country. The aura of New York sophistication could be helpful to ball players who were maligned for spending time playing a children's game. If you can point to New York and say this is played there, it gives you more credibility.

However, technological achievements and a country still somewhat looking to the East Coast for instruction were not alone in spreading the game. These things help convince people to try a game that is played in New York City as their was certainly respect for a perceived sophistication back east, but it would not make people continue playing the game. It had to be enjoyable as well.

I touched on it slightly in the last chapter review, but I think the spread primarily had to do with this: no soaking, foul balls, and what became the use of a harder ball. With the elimination of soaking, there was no longer a need for a fairly soft ball. No longer worried about injuring a person with a hard one, they could use balls that could travel a greater distance. This is important because there was no longer foul territory. The field would be too collapse with a short distance ball, a harder ball extended the field of play. This meant that you no longer had to be a lean, athletic, and fast person to be able to play. The importance of power and speed became far more balanced.

By balancing power and speed, it enabled a few things that make the game enjoyable. First of all, it increased the population able to play the game. People with body types that are not especially suited for chasing down runners and then soaking them were not well suited for the town ball games. Baseball enabled them to hit the ball far to avoid being chased down as well as allowed them to use their arm to throw at the bases which required less skill than throwing at a moving target. Second, I think it made baseball more enjoyable for spectators. Town ball was a spectacle of players hitting the ball in front of and behind home plate, often intentionally glancing batted balls to go no further than 50 feet. The idea was often just to get to first and successfully get to bases in run downs. If one chose to hit the ball well, it would go about 120 to 150 feet. Town ball was essentially a series of guys chasing each other and hitting them with balls. The Knickerbocker rules lengthen the field and the fans largely enjoyed the long ball. Everyone seems to love a good feat of strength.

What I find interesting is how a major current discussion in baseball is the relative worth of a game relying on good pitching versus good hitting. That is where we are now. Back then, it was about good fielding versus good hitting. Pitchers were considered merely one of the nine fielders. The spirit of the rules primarily limited a pitcher back then to merely serve up balls for batters to hit and fielders to field. Over the next few chapters we are bound to see the development of pitchers changing their own role.

24 September 2011

The Orioles Could Be in the Playoffs Right Now

A potential problem that baseball has during its long season is that there are a great many games that mean next to nothing for the majority of fan bases. About twelve of thirty teams had some hope to make the playoffs on September 1st. By now the group has narrow down to five interesting teams: Red Sox, Rays, Angels, Braves, and Cardinals. Everyone else is too far from each other or has basically sealed up their divisions. Maybe it is a unique season in that there is so little intrigue and maybe a Baltimore-centric bias exists here, but this seems like a fairly common occurrence. Fans of the game may be thrilled, but fans of a team (and I think there are more of them) are not and tune out.

Football, basketball, and hockey recognized similar issues in their respective histories and tried to make the games more broadly interesting by adding the number of playoff teams. It works in football. A single game is actually a good indication of who the better team might be and home field advantage significantly impacts those games. In basketball, I don't think it works as the post-season drags on forever. Basketball seems to require more games to show who is a better team, but it may also simply be a TV money grab. Hockey? I guess it is similar. I do not follow pro basketball or hockey much.

Baseball, on the other hand, cannot do this. Anything can happen in a seven game series as Billy Beane can attest...the Cardinals, too. The best team does not always win in a sport that needs about all 162 games to figure out which teams are the best. Baseball needs a lot of events to say much of anything. Think of it like this...if a running back pulls in 1500 yards in sixteen games, it means a lot. You expect him to be a pretty good running back. If a baseball player hits .350 with power over sixteen games, you are not going to put much stock in it. Even if you look at it as 300 carries, a batter with 300 at bats will fool you. In 2010, Wilson Betemit had 315 plate appearances and a 989 OPS (.385 wOBA). Baseball simply requires a greater sample size, so increasing the number of teams in traditional playoff series will likely not result in satisfying the need to crown a team at the end of the year.

So how do you:

1) Keep the interest of as many teams as possible,

2) Keep the regular season in length,

3) Keep the post-season in length,

4) Give significant advantages to teams that did well during the season, and

5) Respect divisions with greater levels of competition?

Here is my response: Use a weighted system to have the playoffs expanded to twenty teams. This seems absurd and it probably is, but let us use the current September 24, 2011 standings for the AL.

The way this system will work is in this way:

Seed 1: Divisional winner with best outside the division record

Seed 2: Divisional winner with second best outside the division record

Seed 3: Divisional winner with the third best outside the division record

Seed 4-10: Remaining teams in order of best outside the division record.

Playoff Schedule

September 29

Two doubleheaders with seeds 5-10. The doubleheaders will take place in the home stadium of the 5th and 6th seeds. The afternoon game will be played between 7th and 10th or 8th and 9th seeds. The evening game will take place against the home teams (5th or 6th seeds).

This would provide for a pretty exciting day of baseball with the lowest ranking teams having to compete in a difficult situation to advance onward. The afternoon game should be fairly even with the teams both as road teams, but the evening game will be grueling. The afternoon winners will have to deal with fatigue, spent arms in the bullpen, a team with a better record on a balanced schedule, and the disadvantage of being on the road (between an equally matched pair of teams, the home team wins about 53% of the time in baseball).

In the current framework, really only the 5th and 6th place teams here would likely be in a hunt for a wildcard or a weak division championship. This is likely to keep competition fierce as a few more wins could lead to a 4th place rank and outside of this crazy one day setup and a few more losses puts you on the road and in need of sweeping a difficult doubleheader. Likewise, teams at the lower stretch of the bracket are fighting for home field advantage or just the simple chance of getting into the playoffs. I think it would be a great win for baseball to have such a wild and inclusive day of meaningful games as well as the intrigue that would manifest in the weeks before.

September 30 - October 5

The winners of the play in round must then fly off to begin playing the next round as a road team. The play in winners, of course, as allowed to change their rosters as needed. I imagine the play in game would include a great number of relievers. The second round will be a best of five series at the home of the 3rd and 4th seeds. The entire series will be played at these locations. This gives a great advantage for the 3rd and 4th seeds with an extra day off to get their pitchers on the right rest and to give them home field for the entire time. It also gives the 3rd and 4th seeds home dates because in the next round, they will have them.

October 6 - October 11

The winners of the second round will fly off to the home stadiums of the 1st and 2nd seeded teams. This too will be a five game series with the top seeds having the luxury of the entire series at home. This gives advantages to being the 1st or 2nd seeded team as they get an entire week off to get their pitchers in order and heal minor injuries. They also retain home field advantage throughout this series and maintain the gate they would have seen in the current format.

October 12 - October 20

The League Champion Series would work the same way as it does now.

October 22 - October 31

The World Series would work the same way as it does now.

The current standings using this format:

1: New York Yankees (.625 outside of division; 45-27 outside of division)

2: Texas Rangers (.540; 47-40)

3: Detroit Tigers (.522; 36-33)

4: Boston Red Sox (.583; 42-30)

5: Toronto Blue Jays (.565; 39-30)

6: Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (.529; 46-41)

7: Tampa Bay Rays (.514; 37-35)

8: Chicago White Sox (.493; 34-35)

9: Baltimore Orioles (.478; 33-36)

10: Kansas City Royals (.472; 34-38)

There only a couple out of division games left as the current schedule is designed to make the most of largely non-existent divisional races. For instance, there are no bubble teams at the edge of the playoffs, but this certainly was not the case a week ago. Now, the Orioles are in the playoffs in this scenario because the next two teams outside of the top ten are the Oakland Athletics (.460; 40-47) and the Cleveland Indians (.458; 33-39) who no longer have any outside of the division games remaining. The worst the Orioles can do is .465 if their next two games with Detroit go poorly. The Royals also no longer have outside the division games left. The the Orioles won their next two, they would tie White Sox for the 8th seed.

AL East Division Winner Race

This is actually an interesting race. At the moment, the Yankees and Rays are tied with divisional records of 37-29 with Boston at 36-30. This would be an amazing end of the season. You can see above what it means if the Yankees win. Boston gets a bye and home field advantage in the second round with the Rays being on the road in the difficult first round. If Boston wins the division, then the Yankees get only the first round bye and home field in the second round with the Rays in the same predicament. However, if the Rays win they leap frog several seeds to the third seed with Texas and Detroit moving to the first two seeds. Yankees get the fourth seed and Boston is left with a home field advantage only in the first round. To say this would be exciting would be an understatement.

Conclusion

The first problem here is that I have absolutely no control over this process and I figure none of my readers do as well. That might be the only problem. I do think though that this set up would make baseball far more interesting to most fan bases and provide a fair structure that rewards teams for good play within their divisions and abroad. This may make it easier for free agents who worry about the playoffs to take more of a chance with teams in difficult divisions.

Although when I began this endeavor I never expected the Orioles to be in a position to actually be included in this setup. However, they did surprisingly well (from my perspective) outside of the AL East. I think that I have been relatively without bias here.

Football, basketball, and hockey recognized similar issues in their respective histories and tried to make the games more broadly interesting by adding the number of playoff teams. It works in football. A single game is actually a good indication of who the better team might be and home field advantage significantly impacts those games. In basketball, I don't think it works as the post-season drags on forever. Basketball seems to require more games to show who is a better team, but it may also simply be a TV money grab. Hockey? I guess it is similar. I do not follow pro basketball or hockey much.

Baseball, on the other hand, cannot do this. Anything can happen in a seven game series as Billy Beane can attest...the Cardinals, too. The best team does not always win in a sport that needs about all 162 games to figure out which teams are the best. Baseball needs a lot of events to say much of anything. Think of it like this...if a running back pulls in 1500 yards in sixteen games, it means a lot. You expect him to be a pretty good running back. If a baseball player hits .350 with power over sixteen games, you are not going to put much stock in it. Even if you look at it as 300 carries, a batter with 300 at bats will fool you. In 2010, Wilson Betemit had 315 plate appearances and a 989 OPS (.385 wOBA). Baseball simply requires a greater sample size, so increasing the number of teams in traditional playoff series will likely not result in satisfying the need to crown a team at the end of the year.

So how do you:

1) Keep the interest of as many teams as possible,

2) Keep the regular season in length,

3) Keep the post-season in length,

4) Give significant advantages to teams that did well during the season, and

5) Respect divisions with greater levels of competition?

Here is my response: Use a weighted system to have the playoffs expanded to twenty teams. This seems absurd and it probably is, but let us use the current September 24, 2011 standings for the AL.

The way this system will work is in this way:

Seed 1: Divisional winner with best outside the division record

Seed 2: Divisional winner with second best outside the division record

Seed 3: Divisional winner with the third best outside the division record

Seed 4-10: Remaining teams in order of best outside the division record.

Playoff Schedule

September 29

Two doubleheaders with seeds 5-10. The doubleheaders will take place in the home stadium of the 5th and 6th seeds. The afternoon game will be played between 7th and 10th or 8th and 9th seeds. The evening game will take place against the home teams (5th or 6th seeds).

This would provide for a pretty exciting day of baseball with the lowest ranking teams having to compete in a difficult situation to advance onward. The afternoon game should be fairly even with the teams both as road teams, but the evening game will be grueling. The afternoon winners will have to deal with fatigue, spent arms in the bullpen, a team with a better record on a balanced schedule, and the disadvantage of being on the road (between an equally matched pair of teams, the home team wins about 53% of the time in baseball).

In the current framework, really only the 5th and 6th place teams here would likely be in a hunt for a wildcard or a weak division championship. This is likely to keep competition fierce as a few more wins could lead to a 4th place rank and outside of this crazy one day setup and a few more losses puts you on the road and in need of sweeping a difficult doubleheader. Likewise, teams at the lower stretch of the bracket are fighting for home field advantage or just the simple chance of getting into the playoffs. I think it would be a great win for baseball to have such a wild and inclusive day of meaningful games as well as the intrigue that would manifest in the weeks before.

September 30 - October 5

The winners of the play in round must then fly off to begin playing the next round as a road team. The play in winners, of course, as allowed to change their rosters as needed. I imagine the play in game would include a great number of relievers. The second round will be a best of five series at the home of the 3rd and 4th seeds. The entire series will be played at these locations. This gives a great advantage for the 3rd and 4th seeds with an extra day off to get their pitchers on the right rest and to give them home field for the entire time. It also gives the 3rd and 4th seeds home dates because in the next round, they will have them.

October 6 - October 11

The winners of the second round will fly off to the home stadiums of the 1st and 2nd seeded teams. This too will be a five game series with the top seeds having the luxury of the entire series at home. This gives advantages to being the 1st or 2nd seeded team as they get an entire week off to get their pitchers in order and heal minor injuries. They also retain home field advantage throughout this series and maintain the gate they would have seen in the current format.

October 12 - October 20

The League Champion Series would work the same way as it does now.

October 22 - October 31

The World Series would work the same way as it does now.

The current standings using this format:

1: New York Yankees (.625 outside of division; 45-27 outside of division)

2: Texas Rangers (.540; 47-40)

3: Detroit Tigers (.522; 36-33)

4: Boston Red Sox (.583; 42-30)

5: Toronto Blue Jays (.565; 39-30)

6: Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim (.529; 46-41)

7: Tampa Bay Rays (.514; 37-35)

8: Chicago White Sox (.493; 34-35)

9: Baltimore Orioles (.478; 33-36)

10: Kansas City Royals (.472; 34-38)

There only a couple out of division games left as the current schedule is designed to make the most of largely non-existent divisional races. For instance, there are no bubble teams at the edge of the playoffs, but this certainly was not the case a week ago. Now, the Orioles are in the playoffs in this scenario because the next two teams outside of the top ten are the Oakland Athletics (.460; 40-47) and the Cleveland Indians (.458; 33-39) who no longer have any outside of the division games remaining. The worst the Orioles can do is .465 if their next two games with Detroit go poorly. The Royals also no longer have outside the division games left. The the Orioles won their next two, they would tie White Sox for the 8th seed.

AL East Division Winner Race

This is actually an interesting race. At the moment, the Yankees and Rays are tied with divisional records of 37-29 with Boston at 36-30. This would be an amazing end of the season. You can see above what it means if the Yankees win. Boston gets a bye and home field advantage in the second round with the Rays being on the road in the difficult first round. If Boston wins the division, then the Yankees get only the first round bye and home field in the second round with the Rays in the same predicament. However, if the Rays win they leap frog several seeds to the third seed with Texas and Detroit moving to the first two seeds. Yankees get the fourth seed and Boston is left with a home field advantage only in the first round. To say this would be exciting would be an understatement.

Conclusion

The first problem here is that I have absolutely no control over this process and I figure none of my readers do as well. That might be the only problem. I do think though that this set up would make baseball far more interesting to most fan bases and provide a fair structure that rewards teams for good play within their divisions and abroad. This may make it easier for free agents who worry about the playoffs to take more of a chance with teams in difficult divisions.

Although when I began this endeavor I never expected the Orioles to be in a position to actually be included in this setup. However, they did surprisingly well (from my perspective) outside of the AL East. I think that I have been relatively without bias here.

18 September 2011

CDOBC: But Didn't We Have Fun? Chapter 2

For more about the book club and books on the agenda click here.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | App 1

Chapter 2: The Knickerbockers' Game Becomes the New York Game

As I wrote in the previous entry, baseball was a great collections of different games that pitted batters against fielders and nothing really more. The game was one where the rules changed frequently even when played by the same players from one day to the next. The available fields dictated the play. The number of people attending dictated the play. It was largely the American game if one can allow for game to mean one of seemingly infinite manifestations. Also, it was more commonly referred to as town ball. Baseball was a named that arrived later when bases became commonly used.

On September 23, 1845, the Knickerbockers devised these rules:

The things I find interesting:

1. The rules are to prevent time consuming altercations.

From my view, these rules are not about defining a game, but rather restricting argument. By entering into a contract (which is what this document is), everyone on the field agrees to these rules. I find it fascinating that one of the elements of our current game arose because of adults bickering with each other. Seven of the twenty rules are solely about how to administer the club. Only the remaining thirteen have to do with the game. It seems point of contention have been addressed. The rules detail who is allowed to play, giving priority to those who came up with the game; the basic rules (e.g. how long the game is, what is fair, what is an out); and a way to diffuse arguments (e.g. presence of an umpire). Major aspects of the game are not mentioned. There is no indication of the proper way to pitch a ball or which way you are allowed to run or even how scoring occurs. The negative space of these rules are just as interesting as what is explicit.

2. The elimination of soaking.

Most of the town ball games at the time used a somewhat softer ball (many report light tower shots as those going about 170 feet) that would be used to soak them (throw at them). The game was one where a ball was hit and then you chased down runners to get close to them in order to improve your ability to hit them before they got to a safe area. The game was built on speed and sure-handedness. If you eliminate soaking, then you free yourself to use a harder baseball. A harder baseball means that speed becomes less important as power can open up the field.

3. Establishing the concept of foul territory.

It is often interesting to hear about life in America in the early 1800s. That the burroughs of New York City were in fact separate distinct towns. Some things are just hard to envision. I once was walking through the Maryland Historical Society in Mt. Vernon in Baltimore. I was looking at a painting that was taken from an estate that was roughly where the Methodist church now stands in the square. The painting depicted a craggy rock and a tree on an uncovered hill overlooking the quaint little town that was Baltimore. Times have certainly changed as there are only a few places around there now where you can actually see the Harbor.

Those changing times also affected the game of baseball. As the towns grew into cities, the commons and the undeveloped sand lots grew smaller and smaller. Games like the Massachusetts game required a great deal of space as part of the strategy was to deflect a ball backwards away from the catcher in order to safely get to first. As the free spaces closed, it meant that the playing field needed to be narrowed. The creation of foul territory allowed baseball to be played in smaller open areas. Players could place home plate flush up against a boundary and not worry about balls being in play where roads or buildings lie. It permitted baseball to live on. It permitted the game to be played within the town square for a while longer which enable men to play before work or immediately after as transportation was not easy nor fast.

Another unintended consequence was how this affected the catcher. In the early days of the game, the two most athletic players where the pitcher and the catcher. These two players had to cover ground immediately in front and behind of the batter. With the creation of foul territory, the catcher no longer needed to quickly cover a great deal of range and be able to quickly get the ball near first or to prevent someone from going to second. It was the beginning of making the catcher a largely stationary position.

Chapter 3 will be focusing on how the game according to the Knickerbocker rules began to spread and how that changed the game for much of America.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

Chapter: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | App 1

Chapter 2: The Knickerbockers' Game Becomes the New York Game

As I wrote in the previous entry, baseball was a great collections of different games that pitted batters against fielders and nothing really more. The game was one where the rules changed frequently even when played by the same players from one day to the next. The available fields dictated the play. The number of people attending dictated the play. It was largely the American game if one can allow for game to mean one of seemingly infinite manifestations. Also, it was more commonly referred to as town ball. Baseball was a named that arrived later when bases became commonly used.

On September 23, 1845, the Knickerbockers devised these rules:

Those are impressive rules and it is equally impressive that once these rules were made, the club basically was non-existent for about eight years. It is an interesting aspect of history how unlikely it is that these rules became the core standardization for baseball.1. Members must strictly observe the time agreed upon for exercise, and be punctual in their attendance.2. When assembled for exercise, the President, of in his absence, the Vice-President, shall appoint an Umpire, who shall keep the game in a book provided for that purpose, and note all violations of the By-Laws and Rules during the time of exercise.3. The presiding officer shall designate two members as Captains, who shall retire and make the match to be played, observing at the same time that the player's opposite to each other should be as nearly equal as possible, the choice of sides to be then tossed for, and the first in hand to be decided in like manner.4. The bases shall be from "home" to second base, forty-two paces; from first to third base, forty-two paces, equidistant.5. No stump match shall be played on a regular day of exercise.6. If there should not be a sufficient number of members of the Club present at the time agreed upon to commence exercise, gentlemen not members may be chosen in to make up the match, which shall not be broken up to take in members that may afterwards appear; but in all cases, members shall have the preference, when present, at the making of the match.7. If members appear after the game is commenced, they may be chosen in if mutually agreed upon.8. The game to consist of twenty-one counts, or aces; but at the conclusion an equal number of hands must be played.9. The ball must be pitched, not thrown, for the bat.10. A ball knocked out of the field, or outside the range of the first and third base, is foul.11. Three balls being struck at and missed and the last one caught, is a hand-out; if not caught is considered fair, and the striker bound to run.12. If a ball be struck, or tipped, and caught, either flying or on the first bound, it is a hand out.13. A player running the bases shall be out, if the ball is in the hands of an adversary on the base, or the runner is touched with it before he makes his base; it being understood, however, that in no instance is a ball to be thrown at him.14. A player running who shall prevent an adversary from catching or getting the ball before making his base, is a hand out.15. Three hands out, all out.16. Players must take their strike in regular turn.17. All disputes and differences relative to the game, to be decided by the Umpire, from which there is no appeal.18. No ace or base can be made on a foul strike.19. A runner cannot be put out in making one base, when a balk is made on the pitcher.20. But one base allowed when a ball bounds out of the field when struck.

The things I find interesting:

1. The rules are to prevent time consuming altercations.

From my view, these rules are not about defining a game, but rather restricting argument. By entering into a contract (which is what this document is), everyone on the field agrees to these rules. I find it fascinating that one of the elements of our current game arose because of adults bickering with each other. Seven of the twenty rules are solely about how to administer the club. Only the remaining thirteen have to do with the game. It seems point of contention have been addressed. The rules detail who is allowed to play, giving priority to those who came up with the game; the basic rules (e.g. how long the game is, what is fair, what is an out); and a way to diffuse arguments (e.g. presence of an umpire). Major aspects of the game are not mentioned. There is no indication of the proper way to pitch a ball or which way you are allowed to run or even how scoring occurs. The negative space of these rules are just as interesting as what is explicit.

2. The elimination of soaking.

Most of the town ball games at the time used a somewhat softer ball (many report light tower shots as those going about 170 feet) that would be used to soak them (throw at them). The game was one where a ball was hit and then you chased down runners to get close to them in order to improve your ability to hit them before they got to a safe area. The game was built on speed and sure-handedness. If you eliminate soaking, then you free yourself to use a harder baseball. A harder baseball means that speed becomes less important as power can open up the field.

3. Establishing the concept of foul territory.

It is often interesting to hear about life in America in the early 1800s. That the burroughs of New York City were in fact separate distinct towns. Some things are just hard to envision. I once was walking through the Maryland Historical Society in Mt. Vernon in Baltimore. I was looking at a painting that was taken from an estate that was roughly where the Methodist church now stands in the square. The painting depicted a craggy rock and a tree on an uncovered hill overlooking the quaint little town that was Baltimore. Times have certainly changed as there are only a few places around there now where you can actually see the Harbor.

Those changing times also affected the game of baseball. As the towns grew into cities, the commons and the undeveloped sand lots grew smaller and smaller. Games like the Massachusetts game required a great deal of space as part of the strategy was to deflect a ball backwards away from the catcher in order to safely get to first. As the free spaces closed, it meant that the playing field needed to be narrowed. The creation of foul territory allowed baseball to be played in smaller open areas. Players could place home plate flush up against a boundary and not worry about balls being in play where roads or buildings lie. It permitted baseball to live on. It permitted the game to be played within the town square for a while longer which enable men to play before work or immediately after as transportation was not easy nor fast.

Another unintended consequence was how this affected the catcher. In the early days of the game, the two most athletic players where the pitcher and the catcher. These two players had to cover ground immediately in front and behind of the batter. With the creation of foul territory, the catcher no longer needed to quickly cover a great deal of range and be able to quickly get the ball near first or to prevent someone from going to second. It was the beginning of making the catcher a largely stationary position.

Chapter 3 will be focusing on how the game according to the Knickerbocker rules began to spread and how that changed the game for much of America.

17 September 2011

A History of Moneyball

|

| Scott Hatteberg |

Law talks about his first year in baseball with the Blue Jays. He was a pure stats guy and an assistant to Ricciardi who was rather dismissive to scouts. Often Law would be called into the GM's office and Ricciardi would go off on rants on evaluations, such as Eric Hinske. He thought Hinske was a remarkable player who would be a major component of the future Jays' teams. He deemed his scouts foolish for thinking Hinske was an organizational player. At that time, the Jays' front office was a highly biased atmosphere toward scouting. Unfortunately it was behind the curve of other organizations by a few years. Over time Law recognized that their methods were unworkable and subsequently left.

Listen to the podcast, it is a very interesting response given by Law to an email by The Common Man, our friend over at one of our sister blogs on the Sweetspot. What I am about to write are my thoughts on it and takes very,very little (almost nothing) from what Law said.

Unlike running for political office where it is a major hindrance on a career, successful people realize the folly of absolutism and begin to moderate their views. Now, I think many ideas have to be chaotic and overly held onto in order to break through long held traditional views. What winds up occurring is that the first line through is given some notice, but to have lasting power...it will also need a moment of success. The A's success is what many sabermetric minded folks grabbed a hold of and, to their detriment, eschewed traditional approaches to assessing talent. It is common to misunderstand how one single approach that succeeds often will succeed given a certain set of variables and that once that context is removed, the approach needs to be altered. I think it is a major reason why many "Moneyball" teams have failed to equal what the A's did.

In the early to mid 90s, several important people began to see the importance of statistics in baseball and how some skills are being overlooked. I do not know who were the first trailblazers, but most of the lines draw back to Sandy Alderson's crew in Oakland. However, they were not alone. Several clubhouses had elements of this minority held view. The Indians come to mind for me as a front office who had one or two of these guys. In the public sphere, you had guys like Bill James, Pete Palmer, and others who were pushing through the concept that statistics were useful and not being utilized. It was an amazingly rich time where there was probably far more cutting edge information publicly available than proprietary within baseball.

The tide turned with the Oakland A's. Their late 90s and early 00s benefited from some great amateur talent acquisition in the years before. There were proto-Moneyball draftees like Jason Giambi and Ben Grieve who both did well for the A's. There were traditional acquisitions like Miguel Tejada and Eric Chavez. Part of this was an amazing hit on three young pitchers with Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson, and Barry Zito. This combination of recognizing the benefits of a statistical approach, utilizing traditional scouting, and hitting on three pitchers created a vital core whose presence would be felt over roughly a decade in Oakland. This club was set up by the collection of incredible talent and somewhat open mindedness of Sandy Alderson.

When Billy Beane took over, he had some strong ideas as to how to improve upon Alderson's model. He could have gone and hired more scouts and taken the talent competition to every other team or he could go with a statistical perspective and find ways to exploits talent that was not properly valued. Now, I think I am rationalizing this in a backward sense. I imagine what the early tenets of applying statistics in the front office saw this as extraordinary and that other teams were foolish for not seeing it. In this perspective, scouts have "no value" because improved scouting is often a razor thin improvement in the talent you are bringing back. It is monetarily inefficient. Whereas if you cut expenses and turn it over to the sabermetric crowd, you are investing in a field that few teams were doing and even fewer were actually using. In short, Beane read the wave, rode it, and many within that group likely forgot that others will do likewise with the following waves. Beane saw this. He saw others liking what he was doing and he saw that teams like the Blue Jays would commit to it more so than he would.

The A's emphasis on college players in the draft preceded the "Moneyball" draft of 2002 by several years. In fact, it likely happened in 1997. When the ownership changed hands before the 1997 season, the new ownership let it be known that they were no longer going to green light a great deal of money for large free agent contracts. Alderson looked at his amazing collection of talent in scouting and development; and made a decision. He recognized that to maintain a successful organization that he was not going to be able to compete with other organizations and that he had to implement more cutting edge ideas. Alderson turned the A's into a more sabermetric focused franchise. This gave more power to Billy Beane who was an early convert. When Alderson left shortly after implementing this plan, the owners hired Beane to take his place.

What Alderson started, Beane finished and probably in a way that Alderson could not have done himself. The A's drafts began to focus almost solely on college talent. The A's 1997 draft (Alderson's last) included only one high schooler in the first ten rounds. If not for Hudson in the sixth, it would have resulted in 12 picks who would not contribute in MLB. Beane's first draft in '98 was better with Mulder being selected. In '99, Barry Zito was pretty much the lone prize. In '00, no one in the top ten amounted to much, but they did select Rich Harden in the 17th round. The controversial '01 draft resulted in Bobby Crosby, Jeremy Bonderman (which supposedly infuriated Beane), and Dan Johnson. Nothing exceptional, but really not much different from the draft before. In fact, the whole thing about the '02 draft focusing solely on college talent is likely overblown. From '97 to '01, the A's selected six high schoolers in the first ten rounds in total. If anything, what they found out was that a polished college pitcher is a better investment in the first round than an exciting, hard throwing high school pitcher. Outside of that, the returns were not different from any other club.

However, people who commit to ideas often over commit and the A's went all college in the next draft to take advantage of Beane's maneuvering to acquire seven of the first 39 picks. It did not go well, they wound up with Nick Swisher and Joe Blanton. Those two alone made the draft valuable and worthwhile, but the A's were certainly expecting more. Jeremy Brown probably could have been a useful backup, but I think there was a lot of Moneyball pressure on him that he did not handle well. Anyway, we can continue on going through all of these drafts, but the point is clear to me that statistics certainly have their place in the draft although the benefit gained is marginal. A stat-alone approach will not result in drafts that are significantly different from what would be expected on average. As the Blue Jays would find out later, these returns are likely to become more marginalized if more people start taking this approach.

So I never mentioned the second part that made those A's teams successful. The first part again was the draft approach instituted by the previous regime and the unlikely hits on three elite young pitchers. That strong core was supplemented by the second part of the A's success: utilizing statistics in free agency. Part of that emphasis was on the idea that collecting spare parts with certain lines would result in a cheap and fairly successful bullpen. Chad Bradford was the flag bearer for this idea in the novel, but someone like Jeff Tam makes just as much sense. The A's focused on players who were successful at keeping the ball on the ground and they did this while few teams were concerned directly about that. It was a concept that was largely built off of the work Voros McCracken did with DIPS. The other part of his free agent approach was to acquire players who could get on base. Scott Hatteberg was the main focus in the novel for this approach, but again there are others. Guys like Mike Stanley, Randy Valverde, what they thought they had in Johnny Damon, David Justice, and Ray Durham among others.

Of course, the benefit of this approach was dying out too when the book came out. Again teams like the Red Sox, Yankees, Indians, Blue Jays, etc. all took notice and understood what was going on. Statisticians were moving in droves to MLB teams with some teams knowing what to do with them and others not so sure. Some GMs thought that a single stat guy "would replace 10 scouts." At one time and in a limited context, that would be true. However, with many of the teams understanding and using statistics, the margin of success became narrower and narrower. As it showed at the end of the novel (as I remembered it or as I remember thinking after reading it) that Beane knew others were in on this approach and that he had to stay ahead of the curve.

Moneyball for Beane next became a focus on defense. It has been only mildly successful. The team has never gotten much help out of the minors and the returns they had on trading their three elite pitchers did not result in comparable value. To say Moneyball led the MLB team to success is overselling that approach. To say Moneyball did not amount to anything and was merely a product of the Big Three would be underselling it. The truth, quite often most obviously, lies in the middle.

Beane also stepped back from his college only approach. This saw major investment in 2005 in high school talent, but an easily seen direction is not apparent. In 2007 and 2008, the team heavily focused on college players and the drafts since include a smattering of promising high school selections. These selections typically are in the Max Stassi or Ian Krol variety. They are highly talented prospects whose characteristics did not equal their asking price. When you overslot players like that, you are betting that they will be worth that price with development or at least the whole portfolio of overslot talent you acquire will at least be equal to the amount you invested. The new strategy might be one where they are still heavily scouting colleges while giving looks to overslot type talent in high school.

This brings us back to the initial point I had which is that the idea of Moneyball is a fluid concept. The most important number in baseball is cost efficiency. Any team has there own set budget and it is the front office's job to determine how to effectively use that money to bring back wins for their teams and, to some extent, fans in the stands. To do this, you need to be able to assess how talent is being valued in your market and determine if a certain aspect of talent is being undervalued. If a competitor figures out what you figure out, your knowledge becomes somewhat marginalized. If a competitor with significantly better resources finds out the same thing, you can be rest assured that you will be left with the scraps.

In that end, I think it becomes clear that way things work in baseball that it is grossly unfair for teams with revenue streams that pale in comparison to others. This has always been the case. It is a major reason why the Orioles were so successful in the 60s and 70s. Pre-draft the team signed bonus babies left and right. A front office needs luck and an elite level direction to be successful against these high revenue, intelligent clubs. What the Rays have been able to do is incredibly remarkable. What they have done though is being figured out by others and being exploited by teams with better cash streams (e.g. Blue Jays, BoSox). The question then becomes where is the next innovation and is my sad sack team going to be ahead or behind the curve? And, again, this is not anything new.

Moneyball is about one innovation and how a small player can become a big player by exploiting it. Nothing more, nothing less. Sometime this fall or winter, the book club will go back and reread this classic.

15 September 2011

CDOBC: But Didn't We Have Fun? Chapter 1

The first book I have chosen for this book club is one I am currently working my way through. The way in which I plan to go through these chapters is one or two at a time with my general thoughts or ideas. I am not necessarily doing a book report here, but providing a bit of a commentary.

But Didn't We Have Fun? An Informal History of Baseball's Pioneer Era 1843-1870

by Peter Morris

I chose this book as the new beginning for the book club because it gives light to a misconception of what baseball is or at least from where baseball emerged. Originally, Earl Weaver's book was to be first, but I figured that might be a book more readers would want to be prepared to discuss. Weaver is also a bit full of myth wrapped around a core truth. Weaver and his success are in ways a lot like the beginnings of baseball.

Chapter 1: Before the Knickerbockers